"Platonopolis"

is a book about Neo-Platonism written by Dominic J. O'Meara, a philosophy

professor based in Switzerland. Neo-Platonism was a form of Platonism that

flourished from the third to the sixth centuries in the Roman Empire, being

gradually displaced (or even assimilated) by Christianity.

Plato, of course, combined political and philosophical ideas. Indeed, he is most notorious for his political philosophy, as laid out in the dialogue "The Republic". The standard view of the Neo-Platonists, by contrast, is that they had lost all interest in worldly matters, concentrating instead on "divinization", a purely spiritual activity taking place in splendid isolation from the world.

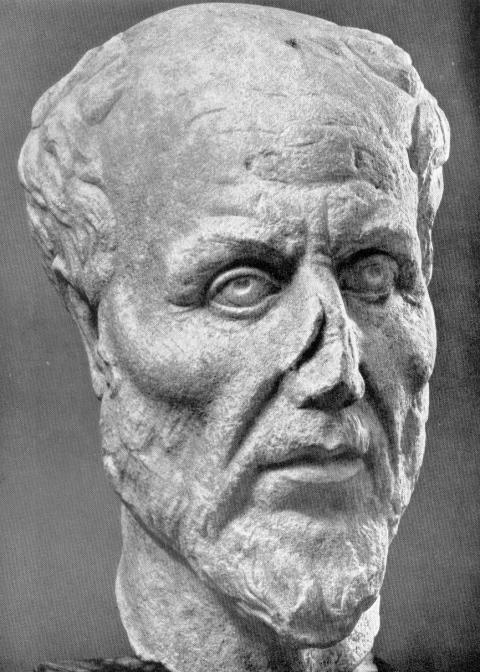

O'Meara argues, quite persuasively, that Neo-Platonists *didn't* lack a political philosophy, and that they weren't completely escapist and contemplative. It's well-known that the Neo-Platonic thinker Plotinus wanted to build a "city of philosophers" in Campania, named Platonopolis in honour of Plato. Most historians consider this a curious quirk in the otherwise contemplative life of Plotinus, perhaps even a mad utopian project. But perhaps Plotinus wasn't mad after all? Perhaps he was actually being consistent?

So how did Neo-Platonist political philosophy look like? O'Meara believes that the seemingly other-worldly concept of divinization actually had political implications. The Neo-Platonists regarded "the political virtues" as a preparatory stage to the "purificatory virtues" by which the soul ascended to the divine. A life of good moral conduct, if possible in the public sphere, prepared souls too immersed in the material world for the next, more contemplative stage. But the Neo-Platonists also believed that the sage who had attained divinization had a duty to return to the world of ordinary mortals in order to guide them. Such guidance might take the form of political action. Thus, Neo-Platonists didn't reject the notion that "the kings should become philosophers, or the philosophers should become kings". Indeed, they regarded such activity as an effect of divinization! Just as God is good and creates the world through overflowing love, so the divinized sage aids his community by proposing better laws, as an example of his overflowing love.

The book then discusses more concrete aspects of Neo-Platonist political philosophy. How did they view Plato's radical idea about philosopher-queens? How did they look at the relationship between Plato's utopia "The Republic" and his more realistic proposals in "The Laws"? What role should religious rituals and sacrifices play in a virtuous community? What is the proper role of punishment?

Of course, most of these discussions were purely theoretical. Emperor Gallienus, perhaps acting under pressure, refused to support Platonopolis, and the project never went off the ground. When the Roman Empire became Christian, pagan philosophers with political ambitions saw their potential scope of action narrowed even more. Julian the Apostate attempted to roll back Christianity, but he was emperor for only three years, too short a time to make any lasting impact. During the reign of Justinian, an anonymous Neo-Platonic writer dared to propose a mixed constitution á la "The Laws", known today only in fragments. The emperor, elected by the leaders of each estate in society, should rule together with a senate. Naturally, Justinian wasn't amused, although the fate of the pamphleteer is unknown.

When reading "Platonopolis", I was struck by several things. First, that the Neo-Platonists had a relatively positive and "rational" view of state and society. I always assumed that Neo-Platonism was similar to Gnosticism, Buddhism and Hinduism. However, the nihilistic renunciation characteristic of at least some strains of these traditions seem absent in Neo-Platonism. There is a tension between the contemplative and the political, to be sure, but the Greek spirit of rational discourse and polis is still present. Even more interesting was that the idea of a mixed constitution survived still during the sixth century, although one wonders how practical it was! Another thing that struck me was that the much-maligned theurgy of Iamblichus was actually *less* obscurantist than standard religious prayers and rituals, and that most Neo-Platonists were "universalists". They interpreted Plato's myth about eternal punishment in Hell for incurable souls symbolically, having instead a notion in which "Hell" was more like purgatory.

If O'Meara is to be believed, the Neo-Platonists were actually a bunch of really rational guys!

Recommended.

No comments:

Post a Comment