Until

the 14th century, science in the Muslim lands and China was more advanced than in

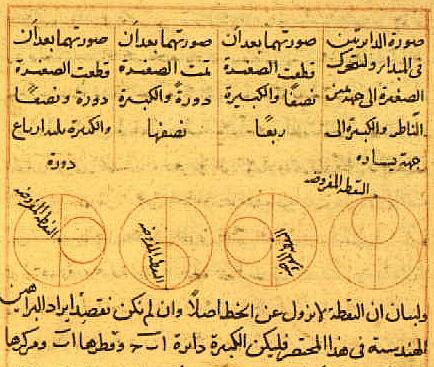

Western Europe. Astronomers in Timurid Iran (of all places!) improved on the

Ptolemaic system with epicycles mathematically equivalent to those used by

Copernicus much later (although they were still geocentrist). That China was

more technologically advanced than Europe still at the time of Marco Polo is

well-known. Yet, around the 14th century, science in both the Muslim lands and

China went into decline, while the erstwhile little backwater of Western Europe

eventually developed modern science.

What went wrong? Or, from a European perspective, what did we do right?

That's the subject of Toby E. Huff's book "The Rise of Early Modern Science". Huff is a British professor who also worked at scholarly institutions in Malaysia (a Muslim nation) and Singapore (a Chinese nation). He writes in the tradition of well-known German sociologist Max Weber, who is most known for his thesis that the ethos of Calvinism somehow gave rise to capitalism. Weber also analyzed other religious traditions and their impact on society. As for Huff, his argument is complex and only a short outline is possible in a review like this. Like the other reviewers, I will concentrate on the chapters dealing with Islam and the West.

Huff doesn't deny that Muslim science was, for centuries, more advanced than European science. Indeed, there was virtually no science at all in the Latin West during the Early Middle Ages. Huff also points out that Muslim science was innovative, the most dramatic example being the previously mentioned astromomical observatory at Maragha in Iran. The eventual decline of Muslim science (except in the field of military technology) cannot therefore be a result of brain drain, lack of innovative thinkers, etc. Something else must be at work here.

What factors could have impeded the rise of modern science in the Muslim caliphates? The author points out that the natural sciences were always seen as "foreign" in the Muslim lands. Many ulama (Muslim scholars) were deeply suspicious of the "foreign" sciences. Muslim jurisprudence, not science, was at the center of Muslim institutions of higher learning. Even Muslim theology (!) was sometimes seen as suspect, since the most conservative ulama feared that it might lead to philosophical reasoning independent of the Quran and the sunna. Eventually, the natural sciences were assimilated with Islam, but as subordinate parts of a largely religious whole. Thus, astronomy was accepted since it could be used to compute the qibla to Mecca, and astronomers became mosque officials. The natural sciences couldn't develop independently.

There were several kinds of colleges in the Muslim world, the madrasas being the most important. However, they didn't function as European universities. The madrasas were religious institutions concentrating on Muslim jurisprudence. Scientific education *did* take place at the madrasas, but not as part of the public curriculum. Rather, instruction in the sciences was given by the teacher in private, often at his own house. A tradition of dissimulation developed, both in regard to science and Greek philosophy. Rather than spreading scientific or philosophical ideas far and wide, they were kept within small, almost esoteric circles. (Jews such as Maimonides had a similar attitude.) Also, instruction at the madrasas was highly personalistic. There was no faculty, and hence no set corporate standards for exams or degrees. Essentially, the student got his degree if and when his personal teacher felt he was ready for it. With the exception of medical science under some rulers, there were no attempts to standardize the degrees over a larger territory.

Huff believes that Muslim society was personalistic and heterogenous. This prevented the rise of the universalist spirit necessary for objective science. In Western Europe, the Roman law was considered binding on all. In the Sunni Muslim lands, there were at least four different schools of jurisprudence, and non-Muslims had their own laws. Since Muslim laws were based on the Quran, the sunna and the consensus among the ulama, innovation was difficult or even prohibited. Since the madrasas concentrated on teaching Muslim law, the ethos of these institutions was one of traditionalism and particularism. It was difficult to develop a universalizing, innovative spirit. Huff further points out that Muslim law didn't recognize corporations as legal persons. A corporate institution with a faculty, such as the European university, couldn't develop under these conditions.

Huff then points out that there was a de facto secular sphere of society in medieval Western Europe, something sadly lacking in the Muslim lands. This secular sphere was created after the investiture conflict, when the papacy and the temporal power had to compromise with each other. Another important factor was the re-discovery of Roman law, which was often seen as secular. The university of Bologna, where Roman law was taught, was purely secular. In the Muslim society, there was no distinction between "church" and state, and hence no neutral space (a central concept for Huff) for potentially subversive scientific exploration and speculation. In Huff's opinion, the Western European universities provided such a neutral space. They were independent corporations, with their own laws and jurisdictions, and some of them were purely secular. Temporal rulers and church authorities did attempt to interfere with the free flow of ideas, to be sure, but the institutionalized independence of the universities made this difficult. Also, high and late medieval society at large was a complex web of guilds, communes, and independent cities, making it well-nigh impossible for a strong, authoritarian center to assume control. In this situation, it was easier for free inquiry to thrive, despite occasional setbacks (the fate of Abelard and Galileo comes to mind). Huff also writes that the science education at European universities was public, rather than secret or semi-secret as in the Muslim territories. Indeed, universities sometimes had lectures open to non-students, at which members of the public at large could ask questions to the professors. This was a far cry from Muslim (or Jewish) esotericism.

Since the author of "The Rise of Early Modern Science" is a Weberian, he naturally believes that religious or ideological factors played an important role in the process. The natural choice would be to contrast Christianity with Islam. However, Huff seems to believe that the crucial ingredient was a rationalist form of Platonism. There was a Platonist renaissance of sorts during the 12th century, and in Huff's opinion it was strongly influenced by Plato's dialogue "Timaeus". From "Timaeus", the philosophers of the Latin West drew the conclusion that the universe is rational, that it follows strict natural laws of cause and effect, and that humans are endowed with a rational mind that can learn to grasp these laws. The analogy between the universe and a machine was used already during the High Middle Ages. Of course, medieval West Europeans still believed that God could miraculously intervene in his creation, as when Jesus was born from a virgin, but this was seen as an entirely different order of events. Under normal circumstances, the universe worked like clock-work according to natural laws graspable by scientific inquiry. Huff also points to the Christian idea of a conscience as a further source of inspiration for the notion that humans have a rational mind, but he admits that Paul might have gotten this idea from popular Platonism. Later, the works of Aristotle would enter the picture as well.

By contrast, Muslim theology was occasionalist. According to this concept, the universe does *not* follow self-contained natural laws created by God at some point in the beginning. Rather, God controls everything directly, from moment to moment. Thus, there is no real causality. That effect necessarily follows cause is an illusion. God wills a certain effect to follow a certain cause at any given moment. He might have willed otherwise. Trying to discover self-contained natural laws (even self-contained natural laws originally created by God) is meaningless. Occasionalism became an insurmountable barrier to modern scientific development in the Middle East.

The Muslims had access to more or less the same empirical facts as the Europeans, as shown by the astronomers of Timurid Iran whose epicycles were mathematically equivalent to those of Copernicus. Indeed, many Muslim libraries were endowed with tens of thousands of books, some of them obviously scientific. Yet, the Muslims never proposed heliocentrism. In Europe, the idea that the natural world wasn't directly dependent on the will of God, but functioned independently, made it possible to propose daring new paradigms such as the Copernican one, even when this seemingly contradicted the literal meaning of Scripture. The neutral space of the universities made it possible for such ideas to get a hearing, especially since education was a public, corporate effort. And since the universities weren't directly controlled by church or state, kings or popes couldn't simply close them down.

In Muslim lands, ulama could issue a fatwa against independent-minded scholars, while a Catholic attempt to stop "heresies" at the university of Paris (the condemnation of 1277) proved ineffectual. The ulama could also mobilize the common man against scholars not of their liking, while universities in Europe were protected by legal privilege from interference by outsiders. In the Latin West, a metaphysical leap to modern science was possible (another central and complex point made by the author), while this proved impossible in the lands of Islam.

"The Rise of Early Modern Science" is well-written, interesting and well-worth pondering. Indeed, I ordered several of the books referenced in the footnotes.

Yet, one question remains. If the Muslims were so bad, how could they develop science for centuries? How was it possible for this non-secular, ulama-ridden, particularistic Muslim society with its wackie jurisprudence to be scientifically leading for 500 years? Indeed, Huff believes that Muslim civilization at its zenith was better even than China!

Why did it work so well for so long? Why did the decline take place during the 14th century? Why not earlier? These are important questions, yet Huff never really answers them. He does suggest some answers in passing, however. One is the ironic observation that science started to decline at the precise moment that it was finally "Islamized". Thus, as long as there was a creative tension between "foreign" science and "Muslim" science, advances were made. The moment "foreign" science became a subordinate part of a non-secular whole, progress stopped. At another point, Huff suggests that al-Ghazali and a 14th century Sufi revival are to blame. However, the theme isn't explored further.

Be that as it may, I give the book four stars.

PS. The chapters on China are, of course, equally interesting.

No comments:

Post a Comment