“Maoist Insurgency since Vietnam” is a book about

leftist insurgency and government counterinsurgency in Thailand, the

Philippines, Sri Lanka and Peru. The author, Thomas A Marks, is a former US

intelligence officer. Despite this, his book is written in a deceptively

objective style. Sometimes, it sounds as if he's advising the rebels! The book

tries to be both empirical and analytical, but I'm not entirely sure if it

succeeds in this. Also, the “Maoist” moniker in the title is misleading, since

the Tamil insurgents in Sri Lanka (including the “Liberation Tigers” or LTTE)

aren't strictly Maoist in ideological orientation. The main problem with the

book is that Marks tries to generalize on the basis of four very different

examples. The political situations in Thailand and the Philippines have certain

similarities, but neither Sri Lanka nor Peru fit the general pattern laid down

by the author. Still, I found his study interesting.

One thing that struck me when reading Marks' study was the dogmatic approach of

the Maoist groups covered. Very often, they attempted to slavishly copy the

Chinese model (“protracted people's war” and “surround the cities from the

countryside”) even when other tactics would have been more effective.

Ironically, this was *not* Mao's approach – he came up with the “Maoist” model

when the Russian model failed in China. The last thing Mao would have wanted

(if I may give some advice to the rebels myself) was for foreign

revolutionaries to copy the Chinese model in nations where circumstances are

very different. This “nationalist” or “exceptionalist” aspect of Maoism seems

to have been lost on the Maoists in Thailand, the Philippines and Peru…

A common mistake was to concentrate on the rural regions even in nations where

many people live in cities, including urban congregations in the rural

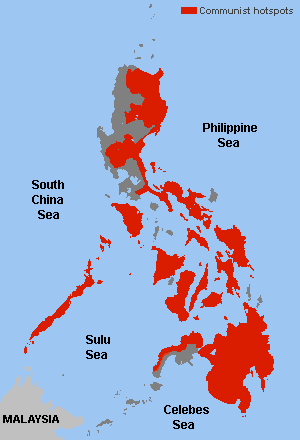

countryside. In the Philippines, the Maoist CPP/NDF/NPA more or less completely

missed the urban-centered struggles which brought down the dictatorship of

Ferdinand Marcos. Despite being a strong rebel group, the CPP was outflanked by

the democratic opposition around Corazon Aquino and the reformist wing of the

military. Another strategic mistake was to continue the armed struggle even

after democratization. In the Philippines, the CPP guerillas launched a full

out offensive against Aquino's democratic government, thereby alienating many

potential supporters. It's also obvious from Marks' study that the Maoist

rebels frequently terrorized civilians in “liberated” areas. The Peruvian

Sendero Luminoso is ill reputed in this regard, but the CPP did pretty much the

same thing, including regular blood purges within its own ranks. The Tamil

insurgents were the worst, competing rebel groups spending considerable time

attacking each other. Due to its nationalist character, the Lankan conflict

also involved ethnic cleansing and foreign intervention.

While the Tamil nationalists were at least fighting “on their own turf”, so to

speak, the Maoists frequently made things hard for themselves by not being

nationalist enough. The Communist Party of Thailand (CPT) was internally split

between a pro-Chinese wing and a pro-Vietnamese ditto. This made the party seem

like an alien element in Thai society. It also created serious friction within

its ranks when Vietnam (backed by the Soviet Union) fell out with China. In

1978-79, Vietnam invaded pro-Chinese Cambodia and Vietnamese troops suddenly

reached Thailand's borders. The fact that China's foreign policy had become

pro-American created additional trouble for the CPT, since the Thai government

they were fighting was also pro-American. Marks further argues that the CPT's

attempts to win a mass following were hampered by their verbal attacks on the

King, their anti-Buddhism and the fact that many of their leaders were

ethnically non-Thai. The CPT eventually bit the bullet and “offered” to form a

“united front” with the military regime against the perceived Vietnamese

threat. However, this could just as well be seen as an adoption to Chinese

foreign policy, rather than a real embrace of Thai patriotism.

The classical response to leftist insurgency is, of course, to repress it with

heavy handed methods. More often than not, this simply fans the flames of the

resistance. During the Cold War, the American approach was apparently to

combine military counterinsurgency with attempts to win people's “hearts and

minds” by social reform programs aimed at the village poor. Thus, aid workers

protected by the military would dig wells, build roads or open up schools.

Another important element was to recruit local villagers to anti-Communist

militias armed by the government. This strategy didn't work very well either.

To Marks, it has to be combined with democratization and actual economic

growth, something the local elites (and US allies) were unwilling or unable to

provide. The author argues that it was democratization which broke the back of

the Filipino and Thai Maoist insurgencies. In Thailand, the policies of the

democratic government also led to economic growth. The ranks of the

pro-government militias swelled, and the Maoists were suddenly confronted with

a kind of “reverse people's war”: the people were armed, but united against

them! Most Maoist recruits were “grievance guerillas”, and with alternative

outlets for their grievances, people's war became less attractive. Ordinary

peasants, attacked by both unruly security forces and Maoist insurgents, were

less willing to put up with the latter if the former disappeared due to

political reforms. Instead, they joined the militias to protect their villages

from Maoist terror.

Marks' analysis sounds convincing when applied to Thailand and the Philippines,

but when he proposes something similar for Sri Lanka, he falls short. The civil

war in Sri Lanka was a fierce nationalist conflict between the Sinhalese and

the Tamil, and therefore cannot be solved by democratization (Sri Lanka is

already a democracy), nor by social reforms (since the poor are split along

ethnic lines, they will continue fighting each other over the spoils of the

reforms). Theoretically, the conflict could of course be solved by granting the

Tamils national independence or autonomy, but since that is precisely what the

Sinhala perceive as a threat to their Buddhist holy land, it's not very likely

to happen either. Indeed, it hasn't – since the book was written, the

Sinhala-dominated Lankan government have solved the conflict by brutally

suppressing the Tamil LTTE. The conflict in Sri Lanka has strong resemblances

with the Israeli-Palestine ditto, which is notoriously intractable. It's also

weirdly similar on a symbolic level: the Sinhala, who were supported by Israel,

see Sri Lanka as the chosen land of the Buddha threatened by infidels of an

alien race (compare Zionism), while the Tamil groups had contacts with the PLO

and apparently learned the tactic of suicide bombing from the Middle East!

Peru is host to yet another species of conflict. The notoriously weird and

cultish Sendero Luminoso had very little popular support, and managed to become

the scourge of the nation mostly because the central government and its

military weren't able to control the entire territory of Peru. Indeed, in many

areas, the government hardly even had a physical presence, making it easy for

Sendero (or local bandits of various kinds, sometimes allied with the Maoists)

to fill the vacuum. Note also that the Peruvian governments which failed to

suppress the Senderistas were democratic (albeit presiding over a collapsing

economy), while the government which *did* suppress the insurgency was

authoritarian but not particularly reformist (Alberto Fujimori presumably

didn't dig that many wells in Ayacucho).

It would be interesting to read a follow up study. Since the book was

published, a Maoist people's war has been waged in Nepal. Here, the author's

perspective was vindicated: the insurgency stopped when Nepal became a

democratic republic and the Maoists transformed themselves into a legal

political party. Meanwhile, another group of Maoist rebels, the famed Naxalites

in India, seem to be growing stronger year after year, despite India being a

democracy. I know very little about it, but it seems largely based on

“scheduled tribes”, so there could be an ethnic dimension involved. Or too few

wells dug? Finally, there is Colombia, where non-Maoist leftist guerillas have

fought successive governments in Bogota since time immemorial.

Despite my criticism of some parts of this work, I will nevertheless give

“Maoist Insurgency since Vietnam” four stars. It contains interesting facts,

did clarify some things I didn't know or suspected before, and is probably

indispensable reading if the issues covered interest you.

_eating.jpg/1024px-Mountain_gorilla_(Gorilla_beringei_beringei)_eating.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)