“The Origins of American Marxism” is a book published

in 1969 by Monad Press, a subdivision of Pathfinder Press, the publishing arm

of the U.S. Socialist Workers Party. The author, David Herreshoff, worked with

the SWP in the anti-Vietnam War movement. However, since his book doesn't

contain any SWP-ish rhetoric, I assume it isn't an official party statement.

The book is more bland than I expected, although it does mention some pretty

colorful characters. I admit that I bought it mostly because of the subtitle,

“From the Transcendentalists to De Leon”. A Marxist trying to claim Ralph Waldo

Emerson?

Actually, Herreshoff doesn't attempt to claim the sage of Concorde. According

to the author, Emerson did say things that sounded radical, and his sympathies

were with the laborers rather than the employers. However, he lacked faith in

the ultimate revolutionary capacity of the working class, and didn't believe

utopian socialist communes were an alternative either. This led Emerson to

emphasize individual self-improvement as a necessary prelude to collective

action at some more distant point in the future. Another difference between

Emerson and Marx was that the latter regarded the city as more advanced than

the countryside, while Emerson thought the opposite (think Thoreau and Muir).

Herreshoff then discusses Orestes Brownson, another Transcendentalist with

sympathies for the nascent labor movement. Brownson joined the Workingmen's

Party of New York in 1828, one of the first labor parties in the world.

However, his labor radicalism soon run into trouble as he proposed to support

the Democrats (including the slave power in the South) against the Whigs, which

he identified with capitalist interests. To hold the labor-agrarian-planter

alliance together, Brownson opposed abolitionism. Later, he abandoned labor

radicalism (and Emerson's Transcendentalism) altogether, converting to the

Roman Catholic Church. Brownson did support the Union and abolition during the

Civil War, even going so far as to back the more radical Frémont against

Lincoln, but Herreshoff believes that this was a kind of provocation. Brownson

wanted to keep the South in the Union to make the United States more

conservative, and he really wanted to control the Blacks once the war was over

– presumably, he therefore had the same positions as Andrew Johnson! During the

war itself, however, the best way to defeat the Confederacy was through a tactical

alliance with the most radical abolitionists…

Herreshoff devotes an entire section of his book to German émigrés in the

United States, since it was these who brought Marxism with them to the new

world. Many also fought in the Union Army. Joseph Weydemeyer may have been the

first (and only?) U.S. colonel freely disseminating “The Communist Manifesto”

while still in uniform! Friedrich Sorge eventually became the foremost

spokesman of Marxism in the United States, after first going through a

“bourgeois radical” phase as a militant enlightenment atheist. Herreshoff also

mentions Herman Kriege, “the world's first former Marxist”, who broke with Marx

already before the publication of the Communist Manifesto.

The main problem for Marxism in the new world was the weakness of the labor

movement, reflecting the weakness of the working class itself in a still

predominantly agrarian nation. Since any labor party risked being assimilated

by one of the two major parties, or swamped by agrarian populists or “middle class

reformers”, Sorge concentrated on Marxist propaganda and journalism, coupled

with a kind of pure-and-simple unionism which emphasized the economic demands

of the workers rather than more general politics. Once the frontier was closed

and industrial development was in full swing, the objective factors would

change and finally favor socialism, or so Sorge reasoned. Of course, this

didn't stop him (nor Marx) from fiercely supporting the Union during the Civil

War.

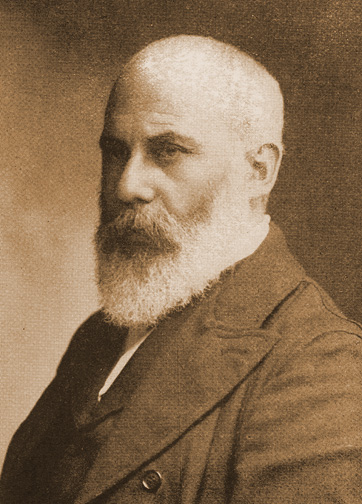

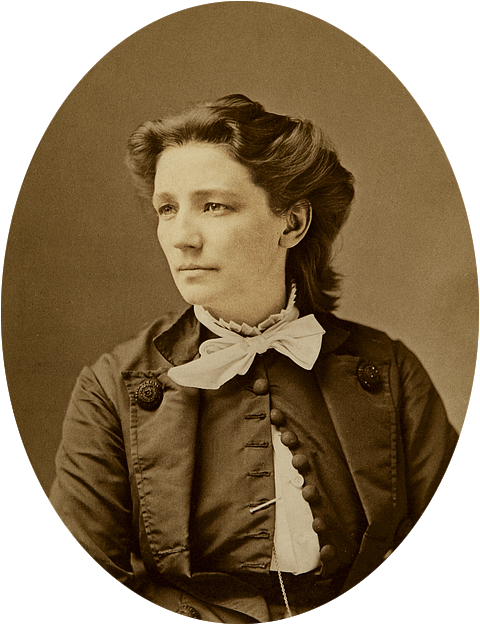

The most peculiar characters mentioned in the book are Stephen Pearl Andrews

and Victoria Woodhull, two Spiritualists (sic) who joined the First

International's American section. The First International (then known as the

International Workingmen's Association) was indeed an international organization

which encompassed most socialist currents (and a few non-socialist ones), and

within which the Marxists had a strong influence. Andrews and Woodhull led what

was essentially a kind of religious sect, with Andrews claiming to be the Grand

Master of all Freemasons in the world and a self-proclaimed candidate for the

papacy in Rome! Some of their proclamations are unintentionally comic, such as

this one: “The Universal Formula of Universological Science – UNISM, DUISM and

TRUISM”. They also proposed the creation of an international language, Alwatol.

However, these crackpots had a political side which was potentially dangerous

for Sorge and the Marxists. Andrews and Woodhull represented the dreaded

agrarianism and “middle class reformism”, in the form of action-oriented

feminism, demands for greenbacks, and support for President Grant's plan to

annex Santo Domingo as a prelude to spread “universal” civilization to the

backward nations. The Spiritualists and their Anti-Pope were eventually pushed

out of the International by Marx, but by then, the organization had already

become moribund.

About half of “The Origins of American Marxism” deal with Daniel De Leon, the

central leader and theoretician of the Socialist Labor Party from circa 1890 to

his death in 1914. The author is surprisingly charitable to De Leon, who is

usually condemned or at least sharply criticized by most currents on the left.

While the first Marxists on U.S. soil had to come to terms with non-labor

radicalism (or worse), De Leon's main problem was “conservatism” in a rapidly

expanding labor movement. De Leon eventually lost that fight, with the SLP

becoming a group with little influence, overtaken by the IWW and the Socialist

Party of Eugene V Debs.

Overall, I get the impression from the book that U.S. Marxism during the 19th

century was a long list of false starts, with the Marxists often retreating

into sectarian self-isolation, rather than uniting with the populists,

reformers and moderate socialists – the only way to get real influence. This is

curious given the fact that Marxists had no trouble supporting the “bourgeois”

Union against the feudal Confederacy, even to the point of calling for unity

around Lincoln rather than backing Frémont.

The author concludes with a rather bland and noncommittal chapter, in which he

bemoans the failure of Marxism to really accommodate itself to American soil,

using the Communist Party as a contemporary negative example. While the author

says relatively little about the “Negro” question in this book, he does seem to

regard it as central, since he here and there criticizes various Marxist (or

“Marxist”) figures for not taking it seriously enough. The book ends with the

hope that the industrial working class will still prove itself to be a dynamic

revolutionary class.

With this, I have to leave you for today.

.jpg)