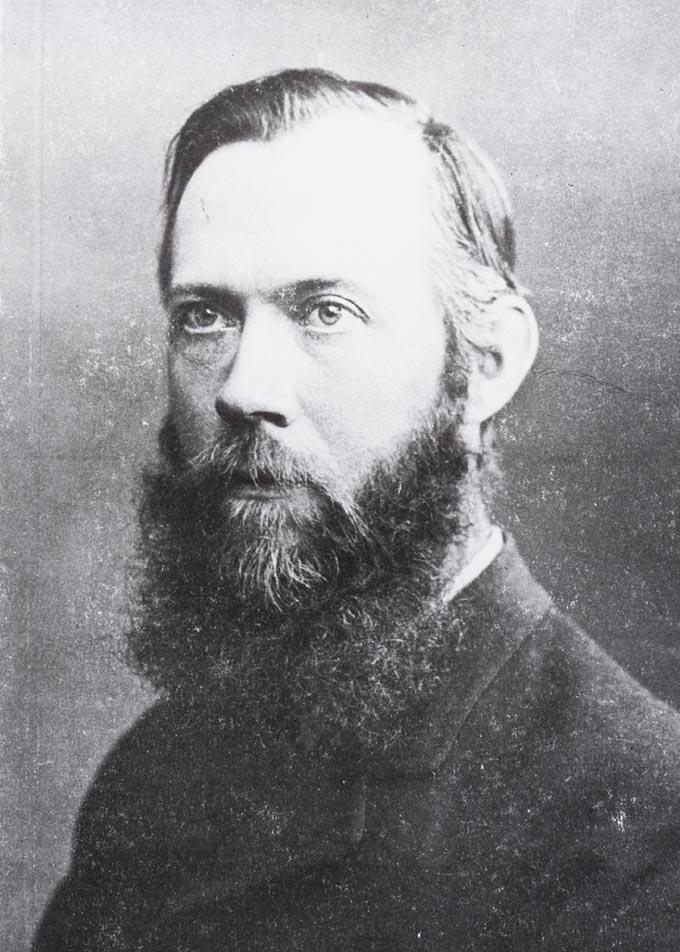

So I´ve continued to read articles by Andrew Reynolds, who must have an interesting

academic position, since his research seems to combine the philosophy of science

with marine zoology. One of his articles on 19th century German

evolutionist Ernst Haeckel (no stranger to marine zoology himself) has the entertaining

title “Ernst Haeckel and the philosophy of sponges”, first published on the web

in 2019.

Sponges (Porifera) are classified as animals, but are extremely

primitive compared to more regular Animalia. Once it became clear to the

scientific community that sponges are *some* kind of animals (they react to

outer stimuli, they feed, they have sperm and ovum), studies of said creatures

became important to understand the early evolution of life.

The curious expression

“The Philosophy of Sponges” actually comes from Haeckel himself and is taken

from his three-volume work on calcareous sponges. Apparently it was in this

magnum opus the giant of evolutionary biology first proposed his controversial

thesis that “ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny”. He also attempted to prove

evolution empirically and specifically, not just lay out an argument in general

terms (as Darwin had already done). And yes, Haeckel also wanted to demonstrate

the truth of his “philosophy of monism” and pin down the exact place of humans

in the cosmos. Quite the agenda for a work on primordial invertebrates, but

there you go. In case you think the whole thing sounds very…I don´t know…*German*,

Romantic, Goethean, something, well yes, that´s probably it! Reynolds quotes William

Blake´s saying about seeing the universe in a grain of sand…

Since Reynolds knows his poriferan biology by heart, the article is

frankly hard to read, but it´s clear that “philosophy” for Haeckel encompassed

both scientific methodology and an entire worldview. But then, that was

probably how the word was often used at the time (compare Romantic

Naturphilosophie of earlier German generations). Haeckel emphasized that scientists

must do both rigorous empirical observations and theory-building, which sounds

obvious today, but probably was a relatively new idea at the time. Thus,

Haeckel and other scientists had to delineate themselves from both the overly-speculative

Naturphilosophen and equally over-empirical scientists who only catalogued long

lists of facts but never draw any theoretical conclusions from them (yes, this

was a thing – see “American Science in the Age of Jackson” by George H

Daniels).

Haeckel further wanted to provide what he called an “analytical” proof

for evolution as opposed to Darwin´s “synthetic” ditto (Haeckel used the terms differently

from Kant) by actually demonstrating an evolutionary lineage, rather than just

holding out the mere possibility of evolution being true. “Ontogeny recapitulates

phylogeny” and attempts to prove that sponges were analogous to a specific

stage in the development of animal embryos were all part of this program.

Haeckel was fascinated by sponges since some of them looked heavily transitional

between different groups. And if both human development in the womb and animal

evolution were subject to the same laws, Haeckel´s monist-materialist worldview

was also proven, since there was no need to postulate anything spiritual or

supernatural above these natural processes.

If Haeckel really succeeded is another matter entirely. It could be

argued that he was the last of the Naturphilosophen. His notorious illustrations

of embryos were “idealized” rather than strictly empirical, leading later generations

to accuse him of science fraud. A fact not mentioned by Reynolds is that

Haeckel´s monism has been interpreted as pantheist rather than materialist.

Reynolds does point out Haeckel´s lifelong fascination with Goethe, and suspects

that the German naturalist at bottom saw himself as an artist rather than a

scientist sensu stricto. Haeckel´s scientific theories were his artistic masterpieces,

and like all artists, he didn´t suffer criticism of his work lightly. Reynolds

ends with discussing the reception of the “philosophy of sponges”. Many contemporary

scientists were sharply critical of Haeckel, and it´s clear that he did make

major mistakes, such as assuming that colonies of several sponge species were

really one “transitional species”.

However, Reynolds also quotes modern scientists

who believe that some of Haeckel´s speculations about sponge or animal evolution

might not have been so wrong, after all. It´s also obvious that he had supporters

in his own day, as when the “Challenger” expedition hired him to analyze their

samples of – surprise – sponges.

With that, I end this

little expedition.