I remember the Anarchist Workers Group. In fact, when I visited London years ago, I *almost* attended one of their meetings (don´t remember the name of the borough).

Be that as it may, I read a few issues of "Socialism From Below", the somewhat peculiar magazine of the AWG. I recently found all back issues (only four were ever published, circa 1989-91) on a website humorously called "Splits and Fusions". It made me realize things I had not seen before. The AWG was curious in that it more closely resembled a Trotskyist group (but with anarchoid rhetoric) rather than a anarchist ditto. Indeed, other anarchists loved to hate it. I wondered why the AWG didn´t simply join the SWP. However, it turns out that there was *another* Trotskyist (or Trotskyist-derived) organization the AWG resembled much more closely. Yes, it was the Revolutionary Communist Party (RCP). Digression: the British RCP is a different group than the American RCP (which is Maoist or Maoist-derived).

In fact, the similarities between the AWG and the RCP are so striking, that the former almost comes across as a front operation for the latter! Since several members of the AWG subsequently did join the RCP, I frankly wonder whether some kind of entryism might have been involved? There are certainly hidden codes: several articles in "Socialism From Below" have titles including the words "The Next Step", and an ad for a summer school includes the word "Confrontation". Now, the RCP´s weekly paper was called "The Next Step", and their theoretical journal..."Confrontation".

More to the point, the political positions of the AWG have a strong family likeness to those of the RCP. The Labour Party is a bourgeois imperialist party and must be completely opposed. While this is also an anarchist position, remember that the AWG sounded Trotskyist-inspired. The RCP was perhaps the only British Trotskyist group which opposed voting for Labour even as a tactic. The correct line towards the IRA in Northern Ireland is a form of military but not political support, and national self-determination is for "the Irish people as a whole", code for a united (Green) Ireland. The established campaigns demanding "troops out" are useless, and should be countered with a more militant anti-imperialist campaign. This is at least similar to the RCP´s positions. Countering homophobia, the Embryo Bill and AIDS hysteria is important. The bourgeois state should *not* ban racist and fascist marches, since this would strengthen the state, ultimately endangering the left. Again, very similar to RCP.

AWG began as a split from the anarcho-syndicalist Direct Action Movement (DAM). The AWG rejected the DAM´s dual unionism in favor of a rank-and-file opposition within the existing unions. And then, maybe they really didn´t. The rank-and-file committees called for by the AWG are really "politicized" fronts for the AWG itself. The committees should cut across union divisions, and perhaps even the divide between workers and the unemployed, suggesting that they aren´t rank-and-file union caucuses of the typical kind. Their program should not be confined to union issues alone. At one point, the AWG strongly implies that their projected rank-and-file movement might agitate for the AWG´s line on Northern Ireland.

The RCP had exactly the same approach to union organizing. My take is that the RCP and AWG positions is *really* just another form of dual unionism, a kind of "moderate" version of the Third Period, essentially trying to create a dual union within the union!

The main difference between the AWG and the Revolutionary Communist Party is that the latter group was really "right as to content", despite its ra-ra-revolutionary rhetoric, something the subjectively more leftist AWG doesn´t seem to have understood. Thus, the refusal to let the bourgeois state arbitrate between fascists and anti-fascists was really a libertarian position, while the attacks on the AIDS panic was probably a libertine promotion of "alternative lifestyle choices". The AWG does criticize the RCP´s bizarre pessimism at one point, however.

As already mentioned, the Anarchist Workers Group often took positions usually associated with Leninism and Trotskyism (while nominally sharing much of the anarchist criticism of the same). They are in effect calling for a democratic centralist organization with strong executive committees, but also with faction and tendency rights. The AWG even calls this "a cadre organization"! Such an organization is necessary, not simply for purely technical reasons (swift decisions must be taken when the class struggle moves forward), but for the more fundamental reason that the working class left to itself will never spontaneously develop revolutionary consciousness. Moreover, the working class is split, one layer being a more privileged labor aristocracy. To "politicize" the struggle ("the battle of ideas"), the revolutionary minority must organize itself on a professional basis. This all sounds like an RCP-ish take on Lenin´s "What is to be done".

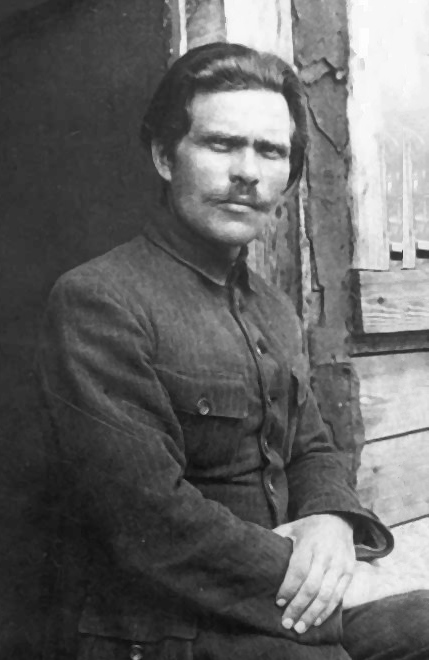

The AWG, however, preferred to reference the so-called Platform, a controversial document adopted in 1926 by Nestor Makhno, Peter Arshinov and Ida Mett, three Russian anarchist exiles in France. Since the Platform calls for the formation of a politically homogenous anarchist organization with a strong leadership, it was roundly condemned by most anarchists as "Leninist". From time to time, some anarchists rediscover the Platform, but the AWG seems to have been the only Platformist group that actually became a kind of crypto-Leninists. Or perhaps crypto-Füredi-ites...

That concludes my admittedly somewhat esoteric reflections.