"Deep Religious Pluralism" is a collection of articles arguing in

favour of religious pluralism from the standpoint of process theology, a

liberal Christian school of thought based on the philosophy of Alfred North

Whitehead. Other important process thinkers include Charles Hartshorne, John

Cobb and David Ray Griffin. While Whitehead and Hartshorne weren't explicitly

Christian, both Cobb and Griffin see themselves as Christian theologians, hence

process "theology".

My, perhaps unkind, summary of Whitehead's "philosophy of organism"

is that it's an evolutionary panpsychism with some kind of god tacked on. Since

Whitehead wasn't an explicit Christian, his ideas can appeal to religious

believers from several different traditions. "Deep Religious

Pluralism" contains contributions from Christians, Muslims, Buddhists and

Jews. Some of them identify explicitly with process philosophy. The

contributors are convinced that Whitehead's philosophy as developed by

Hartshorne, Cobb and Griffin could lay the basis for a robust religious

pluralism.

Ironically, it turns out already in the introductory contributions by David Ray

Griffin that there is a plurality of pluralisms. Griffin is critical of what he

calls identist pluralism, according to which all religions are true in the

sense that they are all directed at one "ultimate", usually

identified with the ineffable Nirguna Brahman of Advaita Vedanta. This is the

perspective of John Hick, who sees himself as a Christian, but also of Huston

Smith, Aldous Huxley and other perennialist writers.

Griffin points out, correctly, that this approach isn't really pluralist at

all, since it assumes that the theistic religions are in error! The personal

god of Christianity is really just an aspect (and in a sense an illusory

aspect) of an even higher, impersonal reality. In order to harmonize

Christianity with religions seeking Nirguna Brahman, the identist pluralist is

forced to heavily reinterpret traditional Christian concepts. Somehow,

"God" becomes identical to Emptiness, and salvation in Jesus Christ

becomes the same thing as moksha (liberation from the wheel of rebirth).

However, these concepts seem to be so far apart, that it's difficult to see how

they can be harmonized without one becoming subordinate to the other. Griffin

is also worried about the ethical implications of Hick's position, since the

Real (to use Hick's term) seems to be beyond good and evil. He also criticizes

Hick for incoherence: if the Real is so ineffable that nothing positive can be

said about it, in what sense could it be a meaningful goal for spirituality at

all?

Griffin's calls his alternative to identist pluralism "deep

pluralism". According to Whithead's process philosophy, there are three

ultimates, not just one: God, creativity and the world. Theistic religions seek

God, while non-theistic religions seek "creativity" (identified by

Griffin with the Mahayana notion of Emptiness or Shunyata). The third ultimate,

the world, is not discussed at length by the contributors to this volume, but I

suppose it could be connected to Wicca, eco-religion or naturalistic pantheism.

In this sense, then, all religions are "true", since they are all

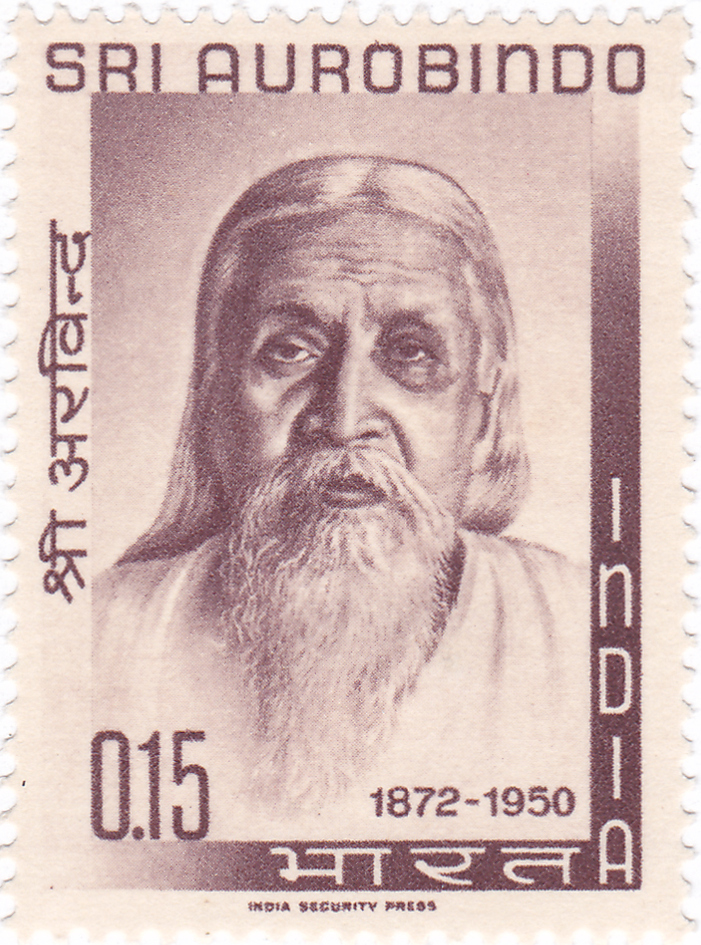

directed at a real ontological ultimate. Griffin points out that Aurobindo had

mystical experiences of all three ultimates, and another contributor mentions

Ramakrishna as another example of a person who could "switch" between

personal and impersonal forms of spiritual realization. Since both Aurobindo

and Ramakrishna were (frankly) pretty wild, I find it almost entertaining to

see them referenced in a work by respectable liberal theologians. But then, perhaps

you need a wild side to realize all three ultimates?

Personally, I found Griffin's articles to be contradictory on several points.

He rejects the eminently sensible proposal that God has two aspects, one

personal and the other impersonal, since no established religion claims this.

This position would therefore make all religions wrong! It would be a kind of

pluralism of ignorance. I beg to disagree. First, some religious thinkers do

seem to believe that the Divine have two aspects of this kind. On a very good

day, Huston Smith takes this position. Aurobindo and Ken Wilber could be other

examples. Second, even if a certain position would make all established

religions wrong, so what? Maybe they are wrong. Process philosophy is

evolutionary, so perhaps our knowledge of the Divine evolves, too. Third,

Griffin's rejection of the Divine having both personal and impersonal aspects

strikes me as incoherent, since *Griffin himself* seems to have a similar

position. While claiming that there are three distinct ultimates, Griffin also

says that the ultimates entail each other. Thus, God cannot exist without

Creativity or the World, anymore than Creativity or the World can exist without

God. In non-process terminology, theism and non-theism are both...well, equal

aspects of the Divine.

Another problem with deep pluralism is that, arguably, there is also a fourth

"ultimate": experiences of the demonic. The process theologians

accept Aurobindo's and Ramakrishna's mystical experiences as empirical evidence

for the three ultimates of Whitehead's philosophy, but Satanists claim that

evil is the ultimate reality, and they too have mystical experiences. Process

theologians would reject these visions, perhaps for ethical reasons. But what

are these ethics based on? The World? Creativity? Even Griffin seems to believe

that ethics are based on the personal god of theism. He quotes Cobb saying that

Emptiness in Mahayana Buddhism is always connected to wisdom and compassion,

two presumably ethical phenomena which Cobb then connects to God. If ethics are

based on God, or the personal aspect of God, this "ultimate" is by

implication higher than the two others. If so, why not say so? Presumably

because saying so would undercut the pluralist project of reconciliation

between personalists and impersonalists. (There's a paranoid fear of being

"imperialistic" throughout this collection.)

Finally, it's unclear what "deep" pluralism entails in practice.

However, it seems that one common strategy is eclecticism. Thus, Steve Odin

attempts to combine True Pure Land Buddhism with process philosophy. (He claims

that they are philosophically identical. I'm not overtly familiar with

"True" Pure Land Buddhism, but the regular version doesn't seem to be

compatible with process philosophy, something pointed out in the very next

article by John Shunji Yokota.) For his part, Yokota attempts to combine Pure

Land Buddhism with Christianity, claiming that Amida Buddha is the Christ.

Sandra Lubarsky promotes the Jewish Renewal Movement, an eclectic neo-Hassidic

movement which she wants to win for process philosophy. Jeffrey Long wants to

create an entirely new form of Hinduism, which he calls Anekanta Vedanta. But

Long is simultaneously a member of the Ramakrishna Mission, the main conduit of

Advaita Vedanta in the West (this is not mentioned in the book, but Long points

it out in a debate here at Amazon). The Muslim writer Mustafa Ruzgar wants to

creatively develop Muhammad Iqbal's philosophy with the aid of process

philosophy.

A pattern is emerging...

When the chips are down, it seems that "deep pluralism" is really the

same thing as Whitehead's philosophy, eclectically combined with different

religious traditions. Often, these traditions are themselves highly eclectic

and entirely modern. This is not necessarily a "bad" thing, but I

fail to see in what sense it's really "pluralist". Rather, it's an

attempt by Whiteheadean-Hartshornites to "imperialize" and change all

other religious traditions. Ironically, Hick or the perennialists - who only

believe in one ultimate - are in a sense more pluralist than Griffin & Co.

They could presumably find traditional esoteric groups in all world religions

and create an ecumenical unity among them, while conceding the exoteric ground

to the exclusivists. Many religious traditions would probably see such an

approach as relatively harmless. For instance, Kabbalism is accepted by certain

strands of Judaism, Sufism is accepted by many Muslims, etc. By contrast, the

deep pluralist process theologians are really trying to create new religious

movements in direct confrontation with the old ones. (Thus, Yokota has great

problems convincing his fellow Buddhists that Amida really is the Christ.)

Personally, I don't mind confrontation per se, but let's be serious for a

change and don't call it pluralism. It's process theology out to conquer the

world, come hell or high water. Whitehead contra mundum.

.JPG/242px-Taxidermy_mounted_tiger_17_June_2021_(10).JPG)

_and_cygnets.jpg)