Gareth Knight (real name Basil Wilby) is a British

Christian esotericist. He is mostly associated with the Society of the Inner

Light, founded by Dion Fortune. Knight has also headed an esoteric group of his

own, today called the Avalon Group. He cites esoterically-inclined Anglican

clergyman Anthony Duncan as one of his foremost influences. “Experience of the

Inner Worlds” was originally published in 1975, during a period when Knight

wasn't a member of the Society of the Inner Light, which may explain why the

book contains some friendly criticism of Dion Fortune's path. Judging by the

book, Knight has found a “hidden master” in C.S. Lewis. Indeed, some of his

arguments are taken almost verbatim from Lewis' writings. I wasn't surprised to

learn that Knight has written an entire book on the magical worldview of the

Inklings, with the obligatory preface by Owen Barfield…

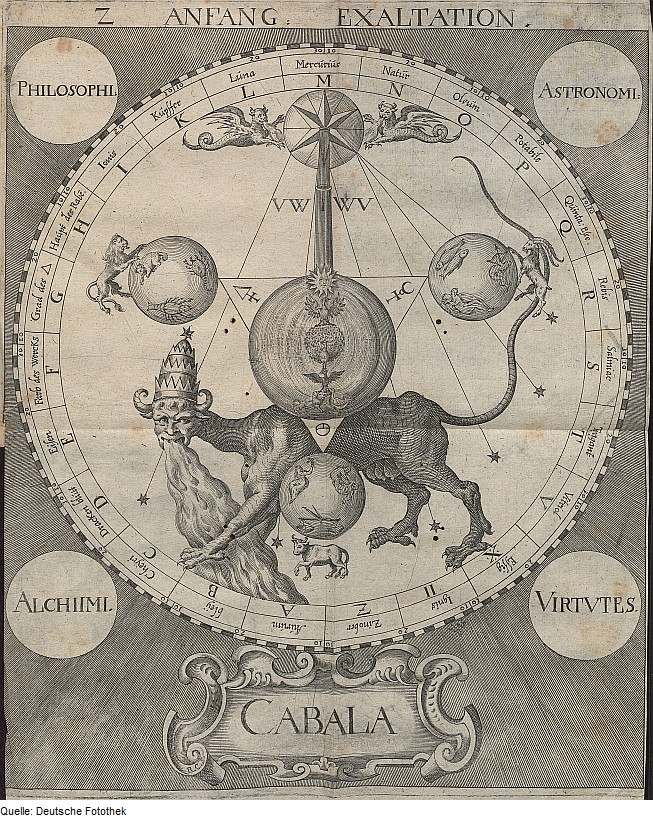

“Experience of the Inner Worlds” is a very interesting book, and many of its conclusions are similar to my own private theological speculations. However, the book is also very uneven. While some chapters can probably be read by beginners, others are more complex and difficult to understand. Perhaps inevitably, these are the chapters dealing with the Qabalah!

Knight is something as surprising as a genuinely Christian esotericist. By “genuine” I mean that he accepts several core Christian doctrines which are usually reinterpreted by other esoteric “Christians”. Thus, Knight accepts what the ecumenical Church councils have decreed concerning the Trinity, the Incarnation, the atonement and the resurrection. He argues at length against “monism” and pantheism. The author's take on panentheism is less clear, but many of his statements sound closer to classical theism. To Knight, God is a loving personal creator who isn't identical to his creation. God has free will and could have decided not to create. Matter isn't evil in itself, humans have experienced some kind of fall (although it's unclear exactly how), the Bible is inspired and Jesus really was God come in the flesh. Knight even uses a version of Lewis' Trilemma to prove his point. The author is less supportive of apocalyptical and millenarian speculations. He accepts reincarnation, this being his most glaring “heresy” compared to traditional-exoteric Christianity. When discussing the sources of Christian esotericism, Knight mentions Ficino and Pico, and he also has a high regard for the Picatrix. He never mentions Boehme, which is interesting. The main repositories of Christian esoteric knowledge, however, are Dante's “Divina Commedia” and the Arthurian legends.

Gareth Knight's take on modern Western occultism is mostly a critical one. He regards Theosophy as the main source of the mischief. Its impersonal view of the divine, obsession with weird cosmological and cosmogonical speculations, and promotion of Krishnamurti as an ersatz Christ figure are all up for criticism. Insofar as Dion Fortune accepted Theosophical doctrines, she is also criticized. Knight believes that most occult “revelations” doesn't come from God, but from something he dubs the Inner Creation, which is roughly identical to the etheric and the astral in other systems. The Inner Creation is the home of countless of spirit-beings, not all of whom are enlightened. Some of them are willfully blind and refuse to evolve towards the divine realm, preferring instead to preach a loveless monist message to human channels and mediums. Genuine angels are part of the divine realm, manifest God's love and affirm the Incarnation. As for magic, its main purpose is to attune the soul to God, although Knight doesn't deny that magic can also be a technique to tap various energies emanating from the Inner Creation.

Concerning mystical experience, the author believes that yoga and similar techniques don't lead to God, but rather to the “basic ground base of universal consciousness”, but this isn't God. He quotes Ruysbroek at length, arguing that the 14th century Flemish mystic was right when criticizing a purely impersonal mysticism during which the mystic completely empties his consciousness and thereby finds “rest”. Ruysbroek's criticism is applicable to Buddhism, Advaita and Neo-Advaita. Various trances and ecstasies aren't proper mysticism either – this would apply to those seeking the kundalini. Proper mystical experience (which Knight controversially compares with sexual union) entails that the soul forgets itself in loving communion with a personal God.

Despite his criticism of other traditions, Knight nevertheless strikes an irenic pose. Taking a cue from Lewis again, he argues that ancient paganism was a preparatio evangelica. Jesus was the allegorical pagan mystery god actually appearing in history. Platonism and Neo-Platonism contain many important truths. Knight approvingly quotes R C Zaehner, who argued that the dividing line between theism and pantheism goes within most religions rather than between them. Just as pantheists can be found in Christianity and Islam, theists can be found within Hinduism. Knight seems to regard such theism as a reflection of the Christian truth. Even heresies such as Gnosticism or Montanism can play a positive role, provided the Church learns to see them as potential correctives to shortcomings of the orthodox, rather than as existential threats to be wiped out. This “Inclusivist” attitude is also similar to that of C.S. Lewis. Knight admits that even Blavatsky's “The Secret Doctrine” can be interesting to study, provided that the seeker doesn't get stuck there!

As already noted, “Experience of the Inner Worlds” also contain sections on magic, Kabbalistic symbols and various meditative exercises. Being the more intellectual type, I preferred the more “theoretical” chapters on theology, but I don't doubt that at least “White” magicians can find something of interest here. In the end I give this book four stars out of five.

No comments:

Post a Comment