David A. Palmer's "Qigong Fever" tells the

strange tale of qigong in the People's Republic of China. The book is a

translated and abridged version of Palmer's original work, published in French.

The perspective is sociological and historical. Palmer has practiced qigong

himself, but is sceptical of the more far-reaching supernatural claims made by

some of its practitioners. Apparently, the author was taught a version known as

the Supreme Mystery of the Venerable Infant!

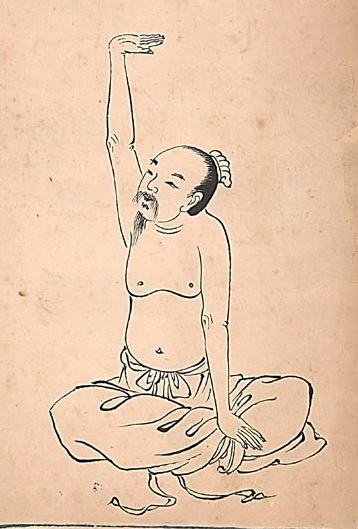

Under Communist rule, popular religion in China was more or less suppressed, while certain forms of institutional religion (including Buddhism and Christianity) remained legal but subject to strict supervision by the Party. The official ideology of the state was atheist and Marxist, and all forms of "superstition" was supposed to be combated and weeded out. However, one form of "superstition" managed to survive and even thrive: the collection of ancient body techniques later known as qigong.

Part of both popular religion, institutionalized religion and (arguably) the dreaded superstition, qigong seemed to have existed in a kind of strange grey area. Luckily, the Communists "discovered" qigong, became convinced of its capability to heal physical ailments, and decided to launch a secularized version of the traditional techniques all across China. Palmer believed that the birth of modern qigong can be pinpointed exactly to 3 March 1949 in the Liberated Zone of Southern Hebei. The Communist cadre responsible for the proclamation was one Huang Yueting, but the real mover behind the new qigong movement was Liu Guizhen, who had been taught some techniques by the old master Liu Duzhou. Guizhen subsequently joined the Communist Party, and "the rest is history".

The official approval of qigong was connected to China's acute lack of doctors trained in modern, Western medicine. It was part of Mao's politics of self-reliance, and thus connected to phenomena such as "barefoot doctors", mass mobilizations of labour power to build dams or exterminate pests, backyard furnaces, etc. Interestingly, qigong was also practiced by party cadre at lush resorts for the Chinese top brass. In many ways, modern qigong was part of the Communist bureaucracy! Like most other "ancient" holdovers, however, qigong was prohibited during the Cultural Revolution. Of course, this didn't manage to extirpate it. Qigong would return, in new and unexpected forms.

Palmer believes that Communist support for secular qigong inadvertently also legitimized its religious and spiritual sides. The experiences of qigong practitioners are difficult or impossible to explain in strictly materialist terms. The techniques had to be learned (at least originally) from traditional masters - witness Liu Guizhen's relation to Liu Duzhou. This created a situation in which the secretive lineages of qigong masters could survive in a kind of legal grey zone, despite the Communist prohibition of popular religion and superstition. The Cultural Revolution had hardly ended when this sectarian form of qigong came out in the open, often practiced in mass fashion in public city parks.

The most curious part of Palmer's story is the "qigong fever" of the book's title, roughly coterminous with the periods dominated by Deng Xiaoping and Jiang Zemin. During this period, official qigong became pretty bizarre. Emphasis was placed on "Extraordinary Powers", in plain English supernatural powers attributed to qigong masters, including psychokinesis, healing by "energy transfer", remote viewing, etc. These supernatural powers were interpreted in a materialist manner, and were said to foreshadow a third scientific revolution. China would become the world leader in this new revolution, ushering in a utopian period of peace and prosperity, while also vindicating traditional Chinese culture against the modern West. If this sounds like Chinese nationalism, scientist messianism or ersatz Maoism, that's because, arguably, it *is* these things.

Palmer believes that the "qigong fever" was an attempt to find or create a credible new ideology in the wake of the failure of traditional Maoism. What surprised me was the strong support these ideas found in the military-industrial complex and scientific establishment of the People's Republic, including among the scientists responsible for developing China's nuclear weapons! But then, similar experiments in parapsychology were also conducted in the United States and the Soviet Union, something used as an argument by the Chinese believers in Extraordinary Powers. Of course, there were critics of the qigong fever as well, who branded the quest for Extraordinary Powers as pseudo-science or, worse, as anti-Marxist. Interestingly, the qigong supporters had such strong support in the Party hierarchy that they managed to silence the critics time and again. When a CSICOP delegation led by James Randi visited China and conducted tests on the qigong practitioners with alleged supernatural powers, the negative results were suppressed by the Chinese authorities for years!

Meanwhile, qigong grew as a popular movement outside the strict control of the Party, with practitioners joining formal networks which soon began to function as virtual denominations. The Party responded by creating a "qigong sector" with officially approved networks, albeit still non-religious (at least formally). The qigong networks were even expected to create local Party committees, educating their supporters in the basics of Marxism-Leninism, combat idealist philosophy, etc! The whole system was based on patronage or "Connections", with high-ranking party officials bestowing favours on the qigong denominations, who in turn were expected to tow the Party line. In practice, this system seems to have worked in qigong's favour, since many of the Party officials charged with controlling the qigong sector believed in the reality of Extraordinary Powers, or at least the efficacy of the body techniques. Palmer analyzes two denominations at length, Zangmigong (based on Tibetan Buddhism but practiced in Manchuria) and Zhonggong, which the author compares with the pyramid schemes that emerged during the market reforms of the 1990's. However, the most sensational movement to evolve during this period was a split from qigong proper: Falungong.

Since Falungong were subsequently suppressed by the Chinese authorities, it's not considered politic to criticize this group. However, I think it's obvious from Palmer's description that we really are dealing with a bizarre cult and a leader, Li Hongzhi, with delusions of grandeur. All the classical traits are there: rejection of all other paths, prohibition to read or even to think about their ideas, opposition to modern medicine, paranoid delusions about demons and extraterrestrial body-snatchers, the idea that Li Hongzhi is the omnipotent and omniscient saviour of the entire universe (i.e. God), the feverish millenarian hopes, etc etc. Falungong are also fiercely sexist and racist. Palmer believes that the rapid spread of this cult was a reaction to the cynicism, hedonism and commercialism of the 1990's. It was a period when honest workers were frowned upon, while all traditional values (both conservative and Maoist-collectivist) were rapidly rejected in favour of individualist self-indulgence. Falungong also spread by making use of a flexible organization outside immediate Party control.

Interestingly, this cult initially infiltrated both the Party hierarchy and the military ditto. In 1999, the authorities had enough and after a series of events which may or may not have been provoked by the intelligence services, Falungong was banned and suppressed. In the atmosphere of repression that followed, the legal qigong denominations were also ordered to disband themselves, effectively putting "qigong fever" to an end.

Is there anything we can learn from the strange story of qigong in the People's Republic of China? I think Palmer hits the nail on its head when he points out (as I noted above) that religion or spirituality simply cannot be suppressed. Even less can it be co-opted by an atheist state for its own purposes. As long as the experiences of the qigong practitioners confirm better with traditional religious or spiritual worldviews, the religious or spiritual aspects of the co-opted body techniques will reassert themselves. Palmer's book also highlights a more disturbing phenomenon: that millenarian expectations don't have to be either religious or secular, but can actually be both, re-enforcing each other. A scientist-paranormal form of messianism is probably even worse than the two pure forms! Reverend Straik and "That Hideous Strength" come to mind, somewhere in the back of my head. Finally, the book shows that a China ruled by Falungong would probably be even worse than the present situation...

"Qigong Fever" is relatively easy to read, although it can be somewhat boring at times - the author is a professor of anthropology and religious studies, after all. Yet, I think it deserves five stars for tackling a subject relatively little known in the West.

No comments:

Post a Comment