“Maroon Societies” was originally published in 1979. This is the new

edition from 1996. The editor, Richard Price, is an anthropologist and

historian with field work experience from Suriname. “Maroon Societies” is a

collection of many different texts, both scholarly and non-scholarly, dealing

with rebel slave communities in the Americas.

The Maroons were runaway Black slaves who had created their own communities out of reach of the colonial authorities and the slave-owners. Marronage existed throughout the American continent from the 16th century to the 19th, when slavery was finally abolished. This, of course, is scarcely surprising. Resistance to slavery is as old as slavery itself. The first Black slave rebellion in the New World took place in 1522 in Santo Domingo against Governor Diego Columbus (the son of Christopher Columbus). The first recorded act of marronage might have been the escape of some Black slaves to join the Indians in 1526 at a Spanish outpost in the territory later known as South Carolina.

The more slavery spread, the more Maroon societies were formed. Some were located deep in the wilderness and were more or less self-sufficient, while others established themselves at the outskirts of slave plantations, often surviving through brigandage. If Maroon communities managed to survive colonial repression, they often established trade relations even with White settlers who were willing to look the other way for a profit. Repression, execution and re-enslavement were the typical reactions of the “proper” authorities to Black marronage, but in areas where the Maroons were too many, the slave power sometimes signed peace agreements with them. A common stipulation of such treaties was that the Maroons had to aid the slave-owners to track down new fugitive slaves!

The Maroon societies were frequently authoritarian. New arrivals were treated as servants or menial laborers during a trial period, until they had proven their loyalty. Defection was punished by death. What is known about Maroon culture point to a mixture of various African traditions, pragmatic knowledge about survival in the wilderness and (sometimes) bits and pieces of Christianity.

The White overlords tried to “divide and conquer”, for instance by pitting Blacks and Mulattoes against each other, by using Indians to track down Maroons, or by promising Black slaves freedom if they participated in punitive expeditions against Maroon settlements. The best soldiers in these anti-Black military expeditions were often Blacks themselves! Conversely, the Maroons attempted to establish cordial relations with the Indians, with varying degrees of success. In some Latin American nations, so-called Zambos are descendants of Black Maroon men and Indian women.

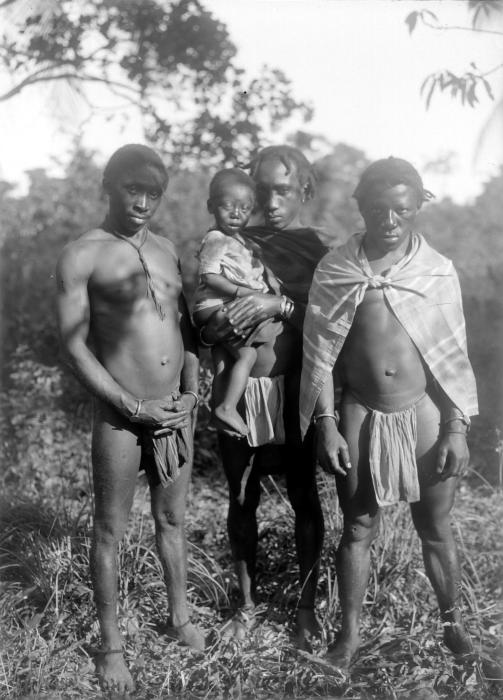

The most long lived Maroon settlement was Palmares in Brazil, which lasted almost the entire 17th century, until it was destroyed by Portuguese troops. After the abolition of slavery, most Maroons slowly integrated into wider society. The foremost exception is Suriname, where the Maroons (known as Bush Negroes) have kept their separate communities and identities until today, forming an ethnic group distinct from other Surinamese Blacks.

“Maroon Societies” doesn't deal with “real” slave rebellions, and therefore mentions Haiti and Demerara mostly in passing. It says relatively little about North America. Neither the Black Seminoles nor the escaped slaves in the Great Dismal Swamp are extensively covered. Most of the material is about Latin America, the Caribbean and Suriname. The collection can be somewhat bewildering to the general reader, and is mostly intended for students, but most of the texts aren't written in a heavy scholarly jargon. For that reason, I think “Maroon Societies” may be of interest to non-academic readers. Four stars.

No comments:

Post a Comment