In this book, the Über-Professor and Ober-Processor of

Whiteheadeanism-Hartshornism-John Cobb Thought, the right venerable David Ray

Griffin, finally decides to take on The Man, the Prophet, Seer and Revelator of

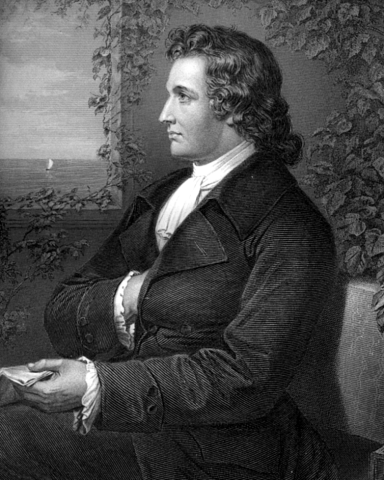

Dornach, the Goethe Redivivus, the one and only Herr Doktor Rudolf Steiner

himself. It's the ultimate conflict, a struggle of titans, a game of thrones,

in which only one can become Number One. The seven worlds clearly aren't big

enough for both Creativity and The Etheric Christ.

And the winner is...

Yeah, like I'm gonna tell you this early in my review! :P

Actually, "American Philosophy and Rudolf Steiner" is a serious or boring work (depending on your reading preferences) in which a number of broadly spiritual scholars attempt to relate American philosophy to Rudolf Steiner, the founder of Anthroposophy. The book is published by Lindisfarne Books together with Steiner Books. The editor is Robert McDermott, who is associated with the Anthroposophical Society, the California Institute of Integral Studies, Lindisfarne and Esalen. "American Philosophy and Rudolf Steiner" is a collection of eight articles, and some of the material was published already in 1991 in the transpersonal magazine ReVision.

I admit that I "only" read four of the essays, skimmed three others and completely skipped the contribution on Dewey. I bought this book mostly because it contains an article by David Ray Griffin, the foremost living expositor of Alfred North Whitehead's process philosophy, with which I have a kind of love-hate relationship. Of course, I also have a similar relation to Steiner. I mean, who hasn't? Griffin commenting on Steiner is something I simply have to read, and I trust some of you would agree...

Overall, however, I feel that the project of relating Steiner to various American philosophers is a dead end. It's like comparing apples with oranges. McDermott almost admits as much in his essay on Steiner and William James. The most relevant comparisons are with Alfred North Whitehead (who was really British!) and Ralph Waldo Emerson, who is regarded as a kind of precursor by the Anthroposophists themselves. Emerson apparently longed for a Teacher, and Steiner's followers believe that this was a prophetic utterance about, well, Steiner. Unfortunately, Gertrude Hughes' essay on Emerson is rather brief and also assumes a lot of foreknowledge about both men (I lack it in Emerson's case). Of course, similarities between Transcendentalism and Anthroposophy are only to be expected, since both currents of thought were inspired by Romanticism. It's much less clear why the other contributors attempt to arrange ersatz dialogues between Steiner and James, Pierce or Dewey, or with postmodern feminism. You might as well attempt a conversation between, say, Richard Dawkins and William Irwin Thompson! Or talk to the cat? A comparison between Thoreau and Steiner is perhaps more relevant, although it would seem that even they were very far apart.

In a collection like this, everyone is bound to have his or her own favourites, but personally I went straight for Griffin's essay on Steiner and Whitehead. I was both a bit disappointed and a bit surprised. I had expected the "respectable" Griffin (at least pre-9/11) to attack Steiner, whose occult musings were anything but respectable. Instead, Griffin strikes a surprisingly irenic pose, and even sounds somewhat "occult" himself. Have we discovered an entirely new dimension of process philosophy? Thus, contrary to my joke above, Griffin doesn't do battle with Steiner. Rather, he attempts a real dialogue, pointing out both similarities, differences and possible areas for further conversation between process philosophy and Anthroposophy. In the process - pun unintended - Griffin acknowledges the immortality of the soul, a kind of teleological evolution, transformation through meditation, the possibility of paranormal phenomena, and a qualified view of precognition. He even delineates a Whiteheadean version of the Akashic Record! It's obvious that while Griffin doesn't accept all the concrete results of Steiner's supposed clairvoyance (nor those of Edgar Cayce, whom he also mentions), he *does* believe that Steiner and Cayce were in touch with higher, spiritual realities.

In process philosophy, the basic particles making up the cosmos are known as "occasions of experience". The act of experience itself is known as "prehension". Griffin has a curious, holographic view of consciousness, in which each occasion of experience prehends *all* previous occasions. In a sense, each particle in the universe experiences the whole of the universe and also the whole of the past! Usually, most of these prehensions aren't conscious. They seem to form something similar to Jung's collective unconscious. At least part of them can be made conscious, however. From this follows that humans have a certain ability to tap into lost or hidden knowledge through seemingly paranormal means. At least in principle, I could access the collective storehouse of experiences, and retell what *you* had for lunch yesterday! Steiner did claim to have precisely such ability, although he used it for less mundane purposes. He believed he could "read" the so-called Akashic Record, a kind of paranormal energy field where all events in the universe have supposedly been "recorded" and still lingers on. Here, Griffin's exegesis of Whitehead's metaphysics lends a certain support to Steiner.

However, Griffin also (rather skilfully) uses the idea of the Akashic Record to criticize Steiner's more outlandish claims. After all, the founder of Anthroposophy did say many strange things about Atlantis, Lemuria, Jesus and the history of the cosmos which have been disproved by modern science or remains unconfirmed. If something like the Akashic Record truly exists (Griffin believes it's really "the consequent nature of God"), not just events but thoughts, dreams and speculations have been recorded. A seemingly objective fact about Atlantis or the hidden years of Jesus might really be a *speculation* about the same, erroneously interpreted as an objective fact by clairvoyants like Steiner. Of course, Steiner believed that his paranormal powers gave him the ability to discern fact from fiction, and that it's possible to grasp purely objective truths, free of distortions. To Griffin, this is not possible. His explanation for this is rather complex, but it's also rooted in Whitehead's metaphysics. Griffin seems to be suggesting that somehow the creativity of the "occasions of experience" makes the cosmos a place of constant flux, making it impossible to completely grasp "the truth" about any single event, such as the life of Jesus. Further, since our conscious experiences are only a small part of our total experiences (not to mention the total experiences recorded in the mind of God), it's impossible to consciously recollect any single event in its entirety. This is a crucial difference between process philosophy and Steiner. Divine revelation or gnosis in the classical senses of those terms is impossible in the process scenario. Steiner, by contrast, believed that his "spiritual science" was strictly empirical and yielded absolute knowledge. Thus, a process philosopher might consider Steiner's ideas to be interesting proposals, but never dogma, gnosis or revealed truth.

Griffin also criticizes Steiner's pantheism, which he contrasts with Whitehead's panentheism (spelled pan-en-theism in the book). His main objection is that pantheism implies that evil and imperfection are part of the divine nature. While Steiner believed that we should choose good over evil, beauty over ugliness, and so on, Griffin feels that he didn't have a firm basis for that belief if *both* good and evil are part of the divine reality. Why not choose evil? In process theology, God is all-good. Evil happens when the occasions of experience strays from God's purposes. Therefore, process philosophy makes it possible to create a consistent ethic centred on choosing the good. A notorious addendum to this position is that God isn't all-powerful. The future is open and there are no guarantees that the good will be victorious. However, Griffin doesn't consider this a problem. Rather, he sees an additional problem with Steiner's position at this point: the pantheist system seems to be determinist. Steiner claimed to have foretold the exact course of the future, which implies that humans don't have free will, something Steiner in other contexts affirmed that we *do* have. If free will is real, which Griffin takes to be the common sense position, then the future isn't preordained, but this also implies that God cannot be omniescent or omnipotent. Griffin does admit a qualified form of precognition, which would entail tapping into God's knowledge of the "structures" of past and present events. These give God an ability to foresee the most likely course of future events. However, he feels that Steiner went much further than this, in a manner similar to the Hebrew prophets who also claimed *exact* knowledge of the future.

Griffin is surprisingly positive to Steiner's meditation exercises, regarding them as an example of genuine transformation to a higher stage of consciousness. What intrigues Griffin seems to be that Steiner didn't want to extinguish emotions or individuality (a position Griffin associates with Buddhism) but rather increase them and thereby achieving love for all of creation and even a kind of evolutionary emergence. Griffin even proposes that this kind of meditation should be incorporated into the spiritual practices of Whitehead's followers. Whitehead himself was an abstract, theoretical thinker and didn't have any practical proposals for a spiritual path.

One point not touched upon by Griffin concerns Steiner's view of Christ. True, the book is about philosophy, not theology or occultism proper. However, since Steiner was at bottom an "esoteric Christian", this is a potentially serious lacuna. The question is: if Anthroposophy is taken as a whole, including the mystical notions about Christ's work at Golgotha, can it *then* become a meaningful partner in dialogue with process philosophy, which is hardly Christian at all, let alone esoteric? Somehow I doubt it, and this might be the main problem with "American Philosophy and Rudolf Steiner" overall. Steiner's occultism was of such a different order from secular philosophy, that a book featuring Catholic, Orthodox or Traditionalist contributors wrestling with Steiner would have felt more relevant...

I'm not sure how to rate this book with its heterogeneous and perhaps misdirected contributions, but in the end I award it the OK rating (three stars).

No comments:

Post a Comment