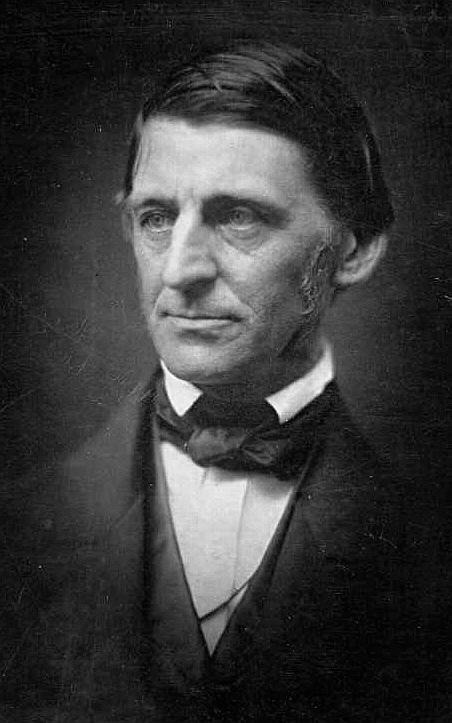

A review of "The Spiritual Teachings of Ralph Waldo Emerson" by Richard Geldard.

The writings of Ralph Waldo Emerson, the founder of

New England Transcendentalism, are notoriously hard to understand. Due to

certain turns of phrase in “Self-Reliance”, his most well known essay, Emerson

is often misunderstood as an individualist bordering the egocentric, something

along the lines of Ayn Rand. Other interpretations include American nationalist

or nature mystic. The author of this book, Richard Geldard, confirms what I

long suspected: while Emerson often expressed himself in the idiom of his day,

he was really a Neo-Platonist and esotericist. Geldard himself is associated with

the University of Philosophical Research, a subdivision of the Philosophical

Research Society founded by prominent esotericist Manly P Hall.

Emerson's “individualism” is really a technique by which the individual discards all the established traditions of his society (including purported religious “revelations”) and looks within himself for the truth. By so doing, the individual discovers the Spirit or the Over-Soul, which is (of course) common to all individuals. He also experiences the Platonic ideas or forms, including the idea of the Good, which lies behind all fleeting phenomena. Emerson's emphasis on freeing the mind is also a Gnostic technique, rather than a call to splendid intellectual self-isolation and armchair punditry. The Over-Soul can only be reached through our minds, but the higher we ascend, the more do our minds conform to the universal spiritual laws of the cosmos. We also realize that whatever happens is for the good and that the universe is in perfect karmic balance.

Emerson seldom discussed who influenced his thinking, since every man must establish the connection with Spirit himself moment to moment, but he did recognize the need for a teacher, and bemoaned the fact that he never found one, while acting as a teacher and guide himself within the small circle of Transcendentalists. Geldard believes that Emerson was strongly influenced by Thomas Taylor's translations and commentaries on Plato's dialogues. He met Carlyle, Coleridge and Wordsworth while visiting Britain. The “Geeta” (the Hindu scripture Bhagavad Gita) was his constant companion.

Interestingly, Emerson wasn't an other-worldly mystic who simply tried to soar the cosmic heights. In many ways, he was a “Descender”, not just an “Ascender”. The material world both hides and reveals the Spirit. In one sense, it's an illusion. In another sense, the world in general and nature in particular, is symbolic and points towards higher truths. This is the ancient Hermetic idea of “as above, so below”, an idea Emerson may have picked up from the writings of Swedish mystic Emmanuel Swedenborg. Since the world is God's garment, the mystic doesn't leave the world. Indeed, humans are the incarnations of God in matter. Guided by conscience, authenticity and courage, the mystic tries to save the world by imparting as much Spirit as possible onto his fellow men. The Spirit-filled man doesn't long for Heaven or personal immortality, but pours out the Spirit where he stands.

Emerson has been criticized for not being consistent on this latter point. He usually refrained from making political statements. Emerson's position seems to have been that little can be done, socially speaking, unless the individuals are changed first. His writings do contain turns which could be interpreted as a callous “Randian” opposition to poor relief and, by extension, the welfare state. However, Emerson wasn't a political reactionary. He opposed slavery and spoke with admiration of John Brown (whom he had met). Emerson's most well known follower Henry Thoreau has been credited with inspiring Gandhi and Martin Luther King. In conversation with Carlyle, Emerson had expressed sentiments similar to those usually associated with Thoreau.

Emerson never “defended” his views through debate or apologetics, believing them to be based on an intuition most people simply didn't posses. He was a “spiritual aristocrat” in that sense. This may explain why he never wrote a popularized introduction to his ideas. Nor did he write a how-to-guide about, say, meditation. We are left with his difficult and hard-to-decode essays. Perhaps the sage of Concord had a point in doing so, but personally, I feel Geldard's book fills a gap. It's not an easy read, unless you happen to be somewhat “tuned in” to these issues, but it definitely does make Ralph Waldo Emerson's Yankee Platonism easier to comprehend. I therefore give it four stars.

No comments:

Post a Comment