I admit that I know next to nothing about Kahlil Gibran (1883-1931), the Lebanese-American writer and Symbolist painter whose most well-known literary work is “The Prophet”, first published in the United States in 1923. According to all-knowing Wiki, “The Prophet” is one of the most popular books ever written, so it´s a bit embarrassing that I literally never heard of it until maybe one or two years ago! I recently read it. It´s available free on the web, and is quite short. It´s not really a “book” sensu stricto, but rather a kind of extended poem. I have no idea what it "really" means, so please take this review with a grain of salt.

The setting of the story is simple. The prophet "Almustafa" has lived in the city of "Orphalese" for 12 years, and must now embark on a ship that will take him back to his home island. The people of the city gather around him one last time to hear his wise preaching on a variety of topics. The rest of the booklet is that preaching. The context strikes me as syncretist. Mustafa means "the chosen one" and is an epithet of Muhammad in Islam, but the prophet´s poetic speech is clearly inspired by Jesus´ Sermon on the Mount. Orphalese itself is pagan, but the people are described as sympathetic to Almustafa´s presence. The city priestess is named Almitra, a reference to the pagan deity Mitra or Mithras. What "Orphalese" itself means seems to be anybody´s guess. A reference to Orpheus, the phallus, or what?

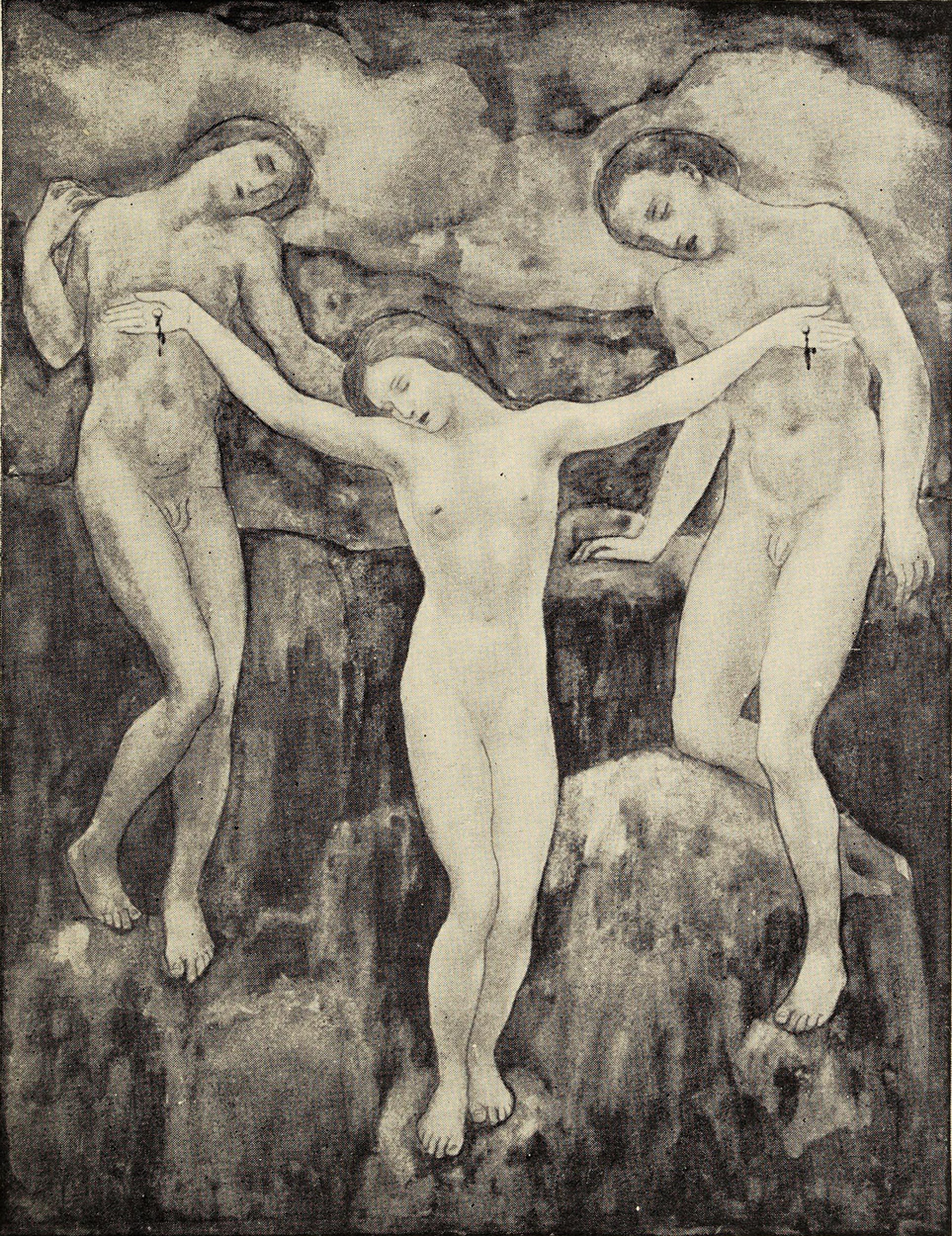

I haven´t bothered trying to decode all of the prophet´s spiritual metaphors, but a few things stand out. The illustrations in the book (made by Gibran himself) are influenced by William Blake´s art. There also seem to be a family likeness with Tarot cards. Almustafa believes in reincarnation, and when he promises to return to Orphalese at some point in the future, rebirth rather than a literal second coming is meant. Also, the "ship" seems to be a symbol for an impersonal divine, so the "journey home" is presumably a temporary merging with the Brahman. Indeed, Almustafa doesn´t seem very keen on going "home"!

The prophet´s sermon does sound Jesus-like at times. Nobody is really evil, in some sense everyone is guilty of the crimes of everyone else, and giving (both material and emotional) is one of the highest goods. Work is also important, but the worker should toil for all members of society, including paupers and poets.

Love trumps all - a love for everyone and everything. Love between spouses is less important, and children should be set free as soon as possible. One striking theme in "The Prophet" is the notion that suffering is inevitable, indeed, it´s somehow part of the good, or even good in itself. This is emphasized again and again.

There is an antinomian tendency in the preaching, since Almustafa clearly doesn´t believe in the efficacy of laws and regulations. Animals and plants are completely free. Earthly pleasure is not rejected, although it must somehow be ultimately transcended. If everyone would be completely pure, there would be no need for clothes or personal grooming?! There is also a pantheist tendency, for instance when the prophet says: "People of Orphalese, beauty is life when life unveils her holy face. But you are life and you are the veil. Beauty is eternity gazing at itself in a mirror. But you are eternity and you are the mirror."

So in summary, we seem to be dealing with a "proto-hippie" sage promoting communitas and liminality, while rejecting most things that *actually* hold society together: romantic marriage, responsible child-rearing, work without promiscuous sharing, a tough attitude towards criminals and (I suppose) streakers...

No wonder "The Prophet" is so popular in California!

Still, there is an additional trait perhaps not present in New Age spirituality: the daring acceptance of suffering and sorrow as inevitable in a completely free existence.

With that, I close my review of Kahlil Gibran´s "The Prophet". Live long and prosper! Or not.

No comments:

Post a Comment