I'm currently reading the ninth volume of Frederick Copleston's "A History of Philosophy", subtitled "19th and 20th century French philosophy". Why, you wonder? And I reply: Why the heck not, really? Here are some preliminary remarks...

Copleston's multi-volume work feels very uneven. Some thinkers are mentioned mostly in passing (Ficino and Pico gets this treatment in the third volume), while other chapters are simply brilliant (Hegel in the seventh volume). Since Copleston was a Jesuit, he often spends considerable time discussing explicitly Christian thinkers.

The volume on French philosophy was published in 1975 and therefore doesn't discuss Foucault, Derrida, Deleuze and the other postmodernists. Thank god! Sartre is included, however. Copleston doesn't limit his overview to "philosophers" sensu stricto. There are sections on De Maistre, Saint-Simon, Proudhon, Fourier, Durkheim and Levi-Strauss. And yes, Teilhard de Chardin! One thinker missing is Georges Sorel.

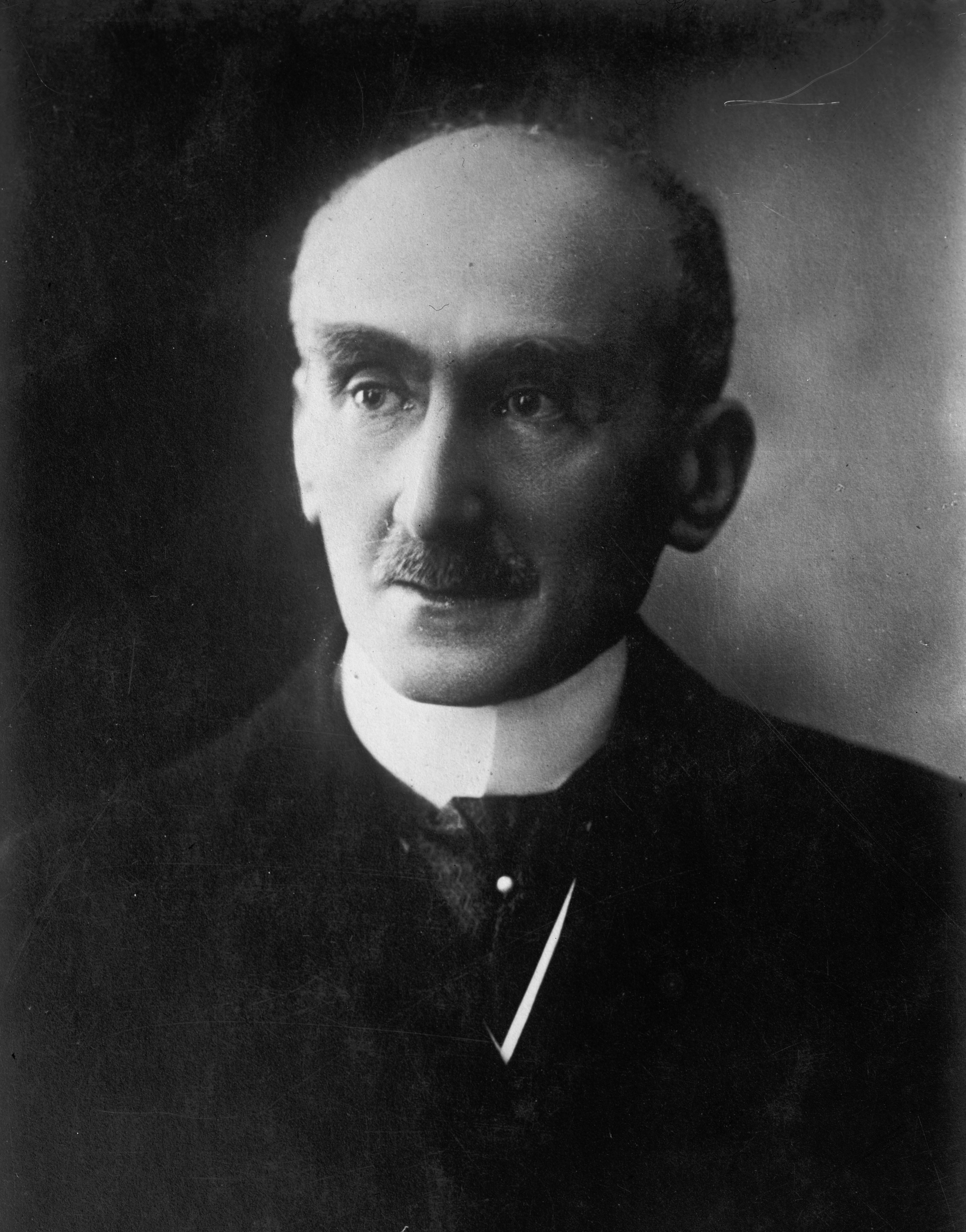

The most fascinating chapters deal with Henri Bergson. I never really understood why mystics (such as Evelyn Underhill) found Bergson's "creative evolution" metaphysically congenial. Maybe they don't. However, Bergson's ideas are strikingly similar to certain spiritual or mystical notions on other points. Even the creative evolution might have a religious equivalent, if we interpret the elan vital as Shakti, the dynamic force of creation in Hinduism. The notion that Reality is "duration" outside space and time, and that "duration" is intuited through introspection sounds like the Hindu notion of Atman being Brahman. And while Bergson didn't regard the "normal" world as pure Maya or illusion, it does seem to be a kind of secondary creation, a static residue, of the foreward-moving thrust of the elan vital.

A problem with Bergson from a mystical viewpoint could be that he was a dualist rather than a monist. The world seems to be bifurcated between "duration" and "extension", or between Spirit and the everyday world of ordinary experience. Ironically, this is similar to some *scientific* interpretations, in which the connection between the little world of subatomic particles and "our" (very different) world is something of a mystery. Copleston never says whether Bergson ever commented on quantum physics!

Later in life, Bergson's thinking took an explicitly pro-religious turn with the publication of "The two sources of morality and religion", reviewed by me elsewhere. Suffice to say, Bergson still had mystical leanings, viewing the development of universal ethics as caused by a kind of mystical inspiration mediated by saints and prophets. Shortly before his death, Bergson wanted to convert to Catholicism, but decided against it for political reasons.

Two other thinkers who fascinated me when reading this tome are Saint-Simon and August Comte. Both represent an early (19th century) form of the Western Idea of Progress in an almost pure, pristine and honest-to-god form. Society must be ruled by the "producers" or the "scientific elite", everything should be strictly "rational" and since that's the case, industrial society will be peaceful and harmonious. QED. Just as nature is controlled by science, there is also a science of society (later known as sociology). To control people, perhaps? Most intriguing is the explicit connection to religion found in both thinkers. While Saint-Simon was a pantheist, Comte seems to have been an atheist who wanted to harness the religious impulse into an organized worship of Humanity through a Positivist Church. I get the impression from Copleston than while Saint-Simon idealized capitalism and the rule of the bourgeoisie, Comte placed scientists (and by implication social engineers) above everyone else. Did he discover "the managerial class" 100 years before it emerged with a vengeance?

Modern industrial society, especially in its properly managed version, does have its upsides, but of course perfect harmony is not one of them, and the idea of actually worshipping it sounds crazy today (although arguably people almost did once). Reading about what illusions some intelligent people harbored about it when it was new, should give us pause. Marx regarded Saint-Simon, Proudhon and Fourier (but not Comte) as utopian socialists, since they didn't see the conflicts inherent in class society or believed it could be abolished by pure rational thinking. Today we know that socialism wasn't free from contradictions either...

And no, I didn't bother reading about Sartre.

No comments:

Post a Comment