.jpg) |

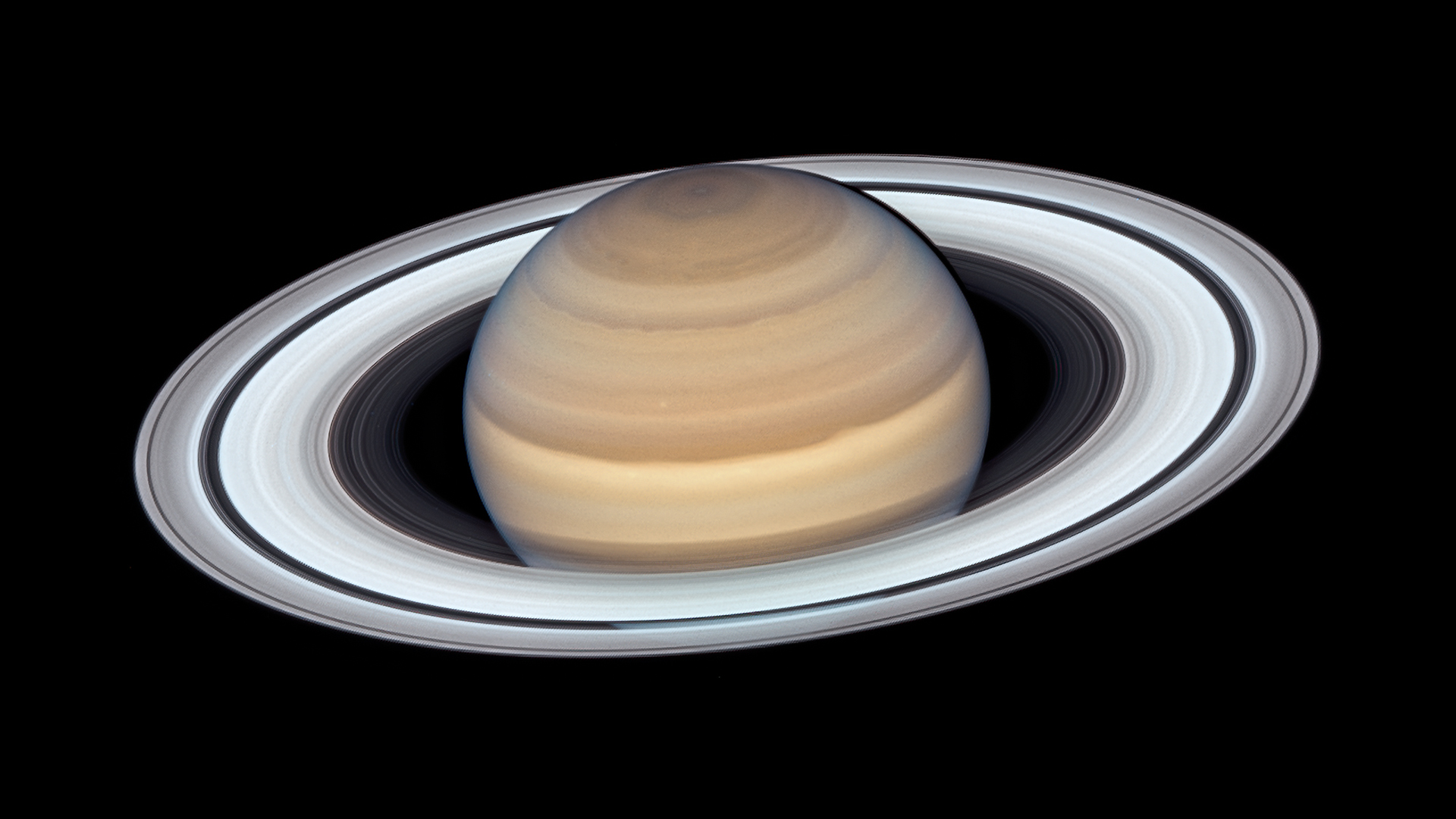

| Gustaf Aulén as Bishop of Strängnäs |

Gustaf

Aulén was a prominent Swedish Lutheran theologian, who eventually became Bishop

of Strängnäs. The English-language “Christus Victor” is his most well known

work. It was originally published in 1931 and is a hybrid between theological tract

and historical study.

Aulén

criticizes the two most widespread views of the Atonement, the “objective”

satisfaction theory associated with both medieval Catholic Anselm of Canterbury

and Lutheran orthodoxy, and the “subjective” view typical of liberal

Protestantism. What both have in common is that they are man-centered. Aulén

believes that the classical view of the Atonement was different from both.

He associates the classical view with most of the Church Fathers, in particular the Eastern Fathers, but also the New Testament writers, Paul in particular. This view is God-centered, God being both the Reconciler and the Reconciled. God enters the world in order to fight the evil demonic powers which keep humans in bondage. The Incarnation, the miracles and the crucifixion are part of the same struggle, which ends in God´s victory over sin, death and the devil. The culmination of the struggle is the resurrection. At no point does God demand “satisfaction” from man (or from Christ´s human side). Man seems to be wholly passive in the drama, God and the demonic “tyrants” being the only actors. The perspective is dualistic, in that God and the Devil are seen as almost equal powers fighting over the rightful possession of man (ultimately, of course, God stands above the Devil).

He associates the classical view with most of the Church Fathers, in particular the Eastern Fathers, but also the New Testament writers, Paul in particular. This view is God-centered, God being both the Reconciler and the Reconciled. God enters the world in order to fight the evil demonic powers which keep humans in bondage. The Incarnation, the miracles and the crucifixion are part of the same struggle, which ends in God´s victory over sin, death and the devil. The culmination of the struggle is the resurrection. At no point does God demand “satisfaction” from man (or from Christ´s human side). Man seems to be wholly passive in the drama, God and the demonic “tyrants” being the only actors. The perspective is dualistic, in that God and the Devil are seen as almost equal powers fighting over the rightful possession of man (ultimately, of course, God stands above the Devil).

Aulén admits

that the classical view had some aspects which may seem weird or even repugnant

to modern Christians. For instance, Jesus was often seen as a ransom *paid to

the Devil* rather than a sacrifice offered up to God. By offering himself as a

substitute for man, Jesus freed humanity from the Devil´s bondage, while

simultaneously cheating the Devil, who didn´t know that Jesus was really God

and could therefore escape his clutches (and destroy the Devil´s dominion). If

this sounds familiar, it should – C S Lewis used these notions as the basis for

his children story “The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe”.

Aulén doesn´t seem to take this colorful language literally, but rather as symbolic descriptions of a mystical reality. Above all, he emphasizes that the Atonement cannot be thought about in rational terms – something Anselm and the Scholastics attempted to do. On Aulén´s interpretation, Martin Luther had the classical view of the Atonement, while later Lutheran theologians (beginning with Luther´s collaborator Melanchthon) once again tried to rationalize it. I assume Aulén preferred the classical view since it emphasizes that the Atonement is wholly an act of grace from God´s side – salvation really is “by grace alone”, whereas the Catholic view gives more leeway to a human-created penitential system. Lutheran orthodoxy is, to Aulén, the most absurd system, being essentially the Catholic system without the penances!

Aulén doesn´t seem to take this colorful language literally, but rather as symbolic descriptions of a mystical reality. Above all, he emphasizes that the Atonement cannot be thought about in rational terms – something Anselm and the Scholastics attempted to do. On Aulén´s interpretation, Martin Luther had the classical view of the Atonement, while later Lutheran theologians (beginning with Luther´s collaborator Melanchthon) once again tried to rationalize it. I assume Aulén preferred the classical view since it emphasizes that the Atonement is wholly an act of grace from God´s side – salvation really is “by grace alone”, whereas the Catholic view gives more leeway to a human-created penitential system. Lutheran orthodoxy is, to Aulén, the most absurd system, being essentially the Catholic system without the penances!

Another

interesting point in Aulén´s exegesis is that the Law is one of the “tyrants”

from which Christ sets men free, alongside sin, death and the Devil. Not only

is the Law incapable of freeing men from sin, it actively leads them away from

such a possibility, being a negative force in its own right. This is obviously

Aulén´s criticism of legalism, although he never mentions what specific groups

he is attacking – something tells me it isn´t Jews or Catholics (tiny

minorities in Sweden in 1931).

One thing that struck me when reading the book is that the classical view of the Atonement as exegeted by Aulén presupposes a view of the world as very radically evil and incapable of change. The world in a sense does legitimately belong to Satan and his host of “powers” and “principalities”. Humans have been snatched away from God´s realm through deceit and are now Satan´s property. From a certain perspective, even God is incapable of simply setting things right by fiat – he must incarnate in the evil world and gradually defeat the “tyrants” one by one, even to the point of suffering and dying. While main-line Christianity wasn´t officially dualist, it´s nevertheless obvious how such a view can morph into Zoroastrian-like dualism or Gnosticism. Even Aulén calls it “dualistic”. In a certain sense, God incarnates in a world which really isn´t his…

One thing that struck me when reading the book is that the classical view of the Atonement as exegeted by Aulén presupposes a view of the world as very radically evil and incapable of change. The world in a sense does legitimately belong to Satan and his host of “powers” and “principalities”. Humans have been snatched away from God´s realm through deceit and are now Satan´s property. From a certain perspective, even God is incapable of simply setting things right by fiat – he must incarnate in the evil world and gradually defeat the “tyrants” one by one, even to the point of suffering and dying. While main-line Christianity wasn´t officially dualist, it´s nevertheless obvious how such a view can morph into Zoroastrian-like dualism or Gnosticism. Even Aulén calls it “dualistic”. In a certain sense, God incarnates in a world which really isn´t his…

According

to the all-knowing Wikipedia, the fate of “Christus Victor” is an interesting

one. The book seems to have inspired both “Paleo-orthodox” Protestants (who I

assume are theologically conservative) and various pacifist and politically

left-wing versions of Christianity. Since Aulén places so much emphasis on the

Eastern Fathers, his work can probably be read with some profit by Eastern

Orthodox believers, as well. The leftists, by contrast, like the idea of Christ

fighting the powers of evil and eventually being executed by them – only to

triumph in the end. Here, the “tyrants” are interpreted naturalistically, as

actual earthly powers oppressing the weak.

With

that, I end my review…and my reflections.

.jpg)