And now, for something completely different. Evolutionary urban legends, anyone?

Is it true that the Irish Elk went extinct due to its gigantic antlers, which made it maladaptive?

That’s a great question — and a classic example of how an old evolutionary myth persists long after science has moved on.

Short answer: No, the Irish elk (Megaloceros giganteus) did not go extinct because its antlers were maladaptive. That theory is outdated.

🦌 Background

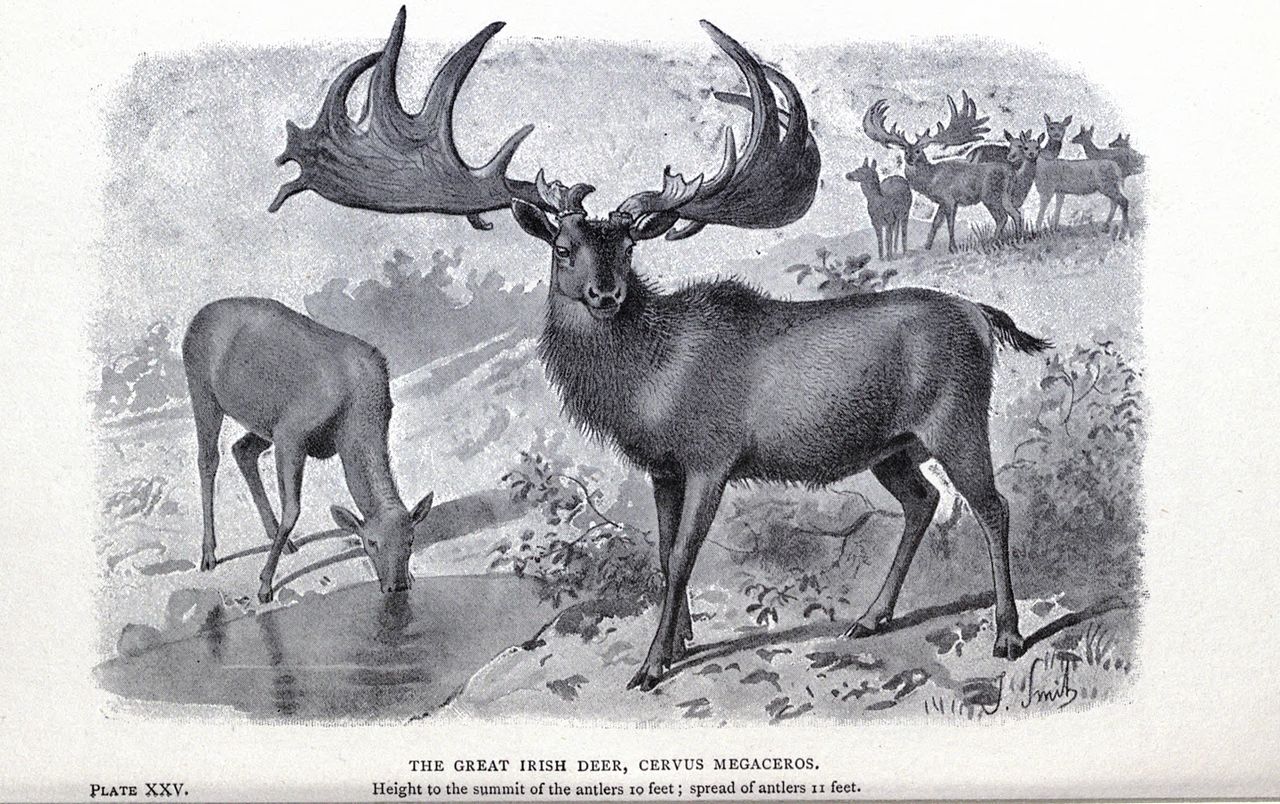

The Irish elk (not actually confined to Ireland, and not truly an elk) was a gigantic Pleistocene deer species, standing about 2.1 m tall at the shoulder, with antlers up to 3.5–4 m across — the largest ever known in any deer.

It lived across Europe, northern Asia, and even into western Siberia, from roughly 400,000 to 8,000 years ago.

❌ The Old “Antler Hypothesis”

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, naturalists like Richard Owen and others argued that:

-

Sexual selection caused males to evolve ever-larger antlers.

-

These antlers became “too large,” making the animals unable to move through forests or escape predators.

-

This runaway trait supposedly led to extinction — a textbook case of maladaptive sexual selection.

It was a neat moral tale about “evolution gone too far,” but the data never really fit.

✅ The Modern View: Environmental & Nutritional Stress

1. Timing of Extinction

The Irish elk survived multiple glacial and interglacial cycles with its huge antlers.

It only disappeared around the end of the last Ice Age (~8,000 years ago) — long after it had evolved large antlers.

2. Environmental Change

At the end of the Pleistocene:

-

Open steppe-tundra habitats (ideal for large grazers) gave way to dense forests and warmer, wetter climates.

-

Their preferred grazing plants diminished.

-

Populations fragmented and shrank.

3. Nutritional Stress & Antler Growth

Large antlers require enormous amounts of calcium and phosphorus each year.

As vegetation changed, mineral deficiency may have made annual regrowth unsustainable.

Antlers in late populations show pathological thinning and incomplete growth — signs of malnutrition, not maladaptation.

4. Human Hunting

Humans were spreading across Europe at that same time, hunting large mammals.

It’s likely that a combination of climate change, food stress, and human predation pushed the species over the edge.

🧠 The Antlers Were Still Adaptive

-

The antlers were sexually selected — displays of strength and genetic fitness, like a peacock’s tail.

-

Biomechanical studies show they were lighter and more efficient than they appear, well-balanced for the neck and skull.

-

The species thrived for hundreds of thousands of years with those antlers — so they clearly weren’t fatal handicaps.

✅ In summary:

The Irish elk went extinct because of rapid environmental change and resource scarcity at the end of the Ice Age — not because its antlers made it maladaptive.

The “antlers-too-big” story is a Victorian myth, not a scientific conclusion.

If you like, I can show how this misunderstanding influenced Darwin and early evolution debates — he actually discussed the Irish elk as a cautionary example in The Descent of Man. Would you like that?

Excellent — this is actually one of the most interesting small episodes in the early history of evolutionary theory, because the Irish elk became a kind of test case for Darwin’s idea of sexual selection, and a lightning rod for critics of evolution in the 19th century.

Let’s unpack it step by step.

🧩 1. The Irish Elk in Victorian Science

In the 1800s, when fossils of Megaloceros giganteus were being dug up from Irish peat bogs and English quarries, naturalists were astonished by its size — especially those massive, ornate antlers.

-

Richard Owen, the famous anatomist and critic of Darwin, called it a “magnificent failure of nature.”

-

For Owen, the Irish elk seemed evidence of “degeneration” — that species could over-specialize and doom themselves.

-

This fit a pre-Darwinian worldview where extinction was seen as a kind of moral or cosmic punishment for excess or imbalance.

The image stuck: the Irish elk as a “fallen aristocrat” of evolution.

🧠 2. Darwin’s Counterargument

When Charles Darwin published The Descent of Man (1871), he was developing his concept of sexual selection — how traits evolve not because they help survival, but because they attract mates.

Critics said: “But what about the Irish elk? Its antlers were so big they must have killed it off!”

Darwin replied (in paraphrase):

The antlers were not fatal — the species lived with them for a very long time. They must have been useful for sexual display and competition.

Extinction likely came from environmental change, not from the antlers themselves.

In Descent, Darwin writes that the idea of “destruction through overdevelopment” is “very improbable,” noting that:

“The structure of no living creature is a mistake in the ordinary sense of the word.”

So, for Darwin, the Irish elk actually supported his theory:

its giant antlers were proof that sexual selection can produce extravagant structures, not that evolution goes wrong.

🧮 3. Why the Misinterpretation Lingered

Even after Darwin, Victorian scientists and artists kept returning to the image of the Irish elk as a tragic over-specialization — partly because:

-

It was visually dramatic and moralistic (“pride before a fall”).

-

It resonated with human anxieties about decadence and progress.

-

It seemed to confirm that “too much beauty” or “too much display” leads to extinction.

So the myth persisted well into the 20th century, long after the evidence said otherwise.

🧭 4. Modern Retrospective

Today, evolutionary biologists view the Irish elk in line with Darwin’s mature understanding:

-

Sexual selection drove its antler size.

-

The trait remained stable for hundreds of millennia, meaning it was adaptive.

-

Extinction was due to ecological shift, not “evolutionary error.”

But the myth still has cultural staying power — the Irish elk as a parable of evolutionary hubris, nature’s “Icarus.”

✳️ Summary Table

| View | Era | Explanation for Antlers/Extinction |

|---|---|---|

| Degeneration Theory (Owen) | mid-1800s | Species over-specialized → self-destruction |

| Darwin’s Sexual Selection | 1871 | Antlers = successful display trait; extinction due to environment |

| Modern Evolutionary Biology | 20th–21st c. | Stable, adaptive morphology + end-Pleistocene climate/human pressure |

In short:

The Irish elk didn’t die because evolution “went too far” — it died because the world changed around it.

But for Victorian thinkers, it symbolized the fear that beauty, pride, or excess might destroy even nature’s noblest creations.

Would you like me to show a few Victorian paintings and illustrations that helped cement that tragic “over-evolved elk” image in popular imagination?

No comments:

Post a Comment