Originally posted as an Amazon "review" of Trotsky´s Transitional Program.

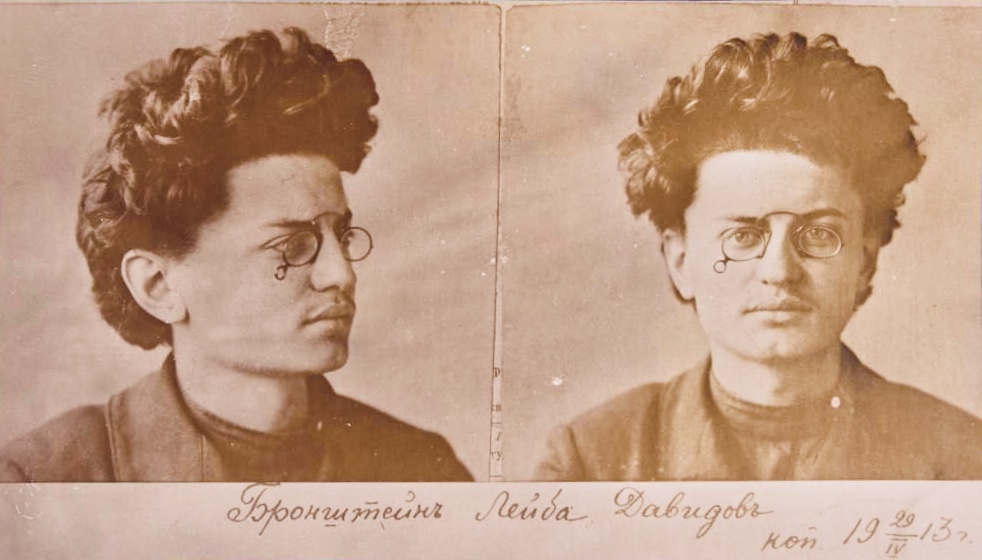

Leon Trotsky was one of the leaders of the October

Revolution and early Soviet Russia. He organized the Red Army and was part of

Lenin's inner circle. That inner group of Bolsheviks also included Zinoviev,

Kamenev, Bukharin and, of course, Stalin. Abroad, Trotsky was often considered

to be Lenin's "number two", and the Bolshevik regime was therefore

often referred to as the regime of Lenin and Trotsky. Yet, after the death of

Lenin, Trotsky was quickly outmanoeuvred and left to fight a loosing factional

battle within the Communist Party. His opposition group was known as the Left

Opposition and, for a time, the United Opposition. In 1929, Trotsky was

expelled from the Soviet Union. He eventually got political asylum in Mexico.

In 1940, Trotsky was assassinated by a Soviet intelligence operative who had

infiltrated his household. He is buried at Coyoacan, a suburb to Mexico City.

Almost immediately after his expulsion from the USSR, Trotsky had begun to organize his own Communist movement, which adopted the name Fourth International in 1938. Although Trotsky never called his movement "Trotskyist" but rather "Bolshevik-Leninist", the term "Trotskyist" was proudly adopted by his supporters at some point after the old man's death. Today, the Trotskyist movement is split in many different organizations with widely divergent politics. Only in three nations did Trotskyism approach something close to mass influence: Vietnam during the 1940's, Sri Lanka during the 1940's and 1950's, and Bolivia during the same period. However, Trotskyism has been an important force on the "far left" in both Western Europe, North America and Latin America.

Trotsky's most important political works are "The Third International after Lenin", "The Permanent Revolution", "The Revolution Betrayed", "Literature and revolution", "The Transitional Program" and "In Defence of Marxism". His autobiography "My Life" is also quite well known.

So what is wrong with Trotskyism, then?

To simplify somewhat, there are basically two kinds of Trotskyists. Let's call them "soft" Trotskyists and "hard" Trotskyists. The former category looks upon Trotsky as a democratic socialist, an advocate of a socialism with a human face, indeed, as the first Soviet dissident. They associate him with "workers' democracy" and artistic freedom. In other words, they paint Trotsky as a democratic opponent of Stalin and Stalinism. Today, the official Fourth International takes this "soft" position. The "hard" Trotskyists, by contrast, emphasize Trotsky's similarities with Lenin: his Communism, internationalism and belief in the international proletariat. In this vision, Trotsky is a revolutionary opponent of Stalinism. Thus, we have a moderate version of Trotskyism, and a more militant version.

TROTSKY AS "DEMOCRAT"...AND DICTATOR

The view of Trotsky as a "democrat" is difficult to take seriously. Trotsky's record while in power, and even afterwards, is hardly that of a "democrat".

During the Russian civil war, Trotsky authored the book "Terrorism and Communism", in which he admitted that effective power in Soviet Russia was in the hands of a small group of revolutionary leaders. He considered this a positive trait of the new regime. Commenting on those who compared Russian War Communism with slavery, Trotsky wrote that even slavery was once historically progressive! It should be noted that this book was translated to many different languages (including Swedish and English) and distributed all around the world. Thus, it enjoyed imprimatur from the other Bolshevik leaders and the Communist International. Today, however, the "soft" Trotskyists never reprint it, and even the "hard" groups usually avoid it as too outspoken. (One exception was the Workers Revolutionary Party in Britain. I have reviewed their edition elsewhere.)

Still, Trotsky's actions speak louder than his words. He proposed the militarization of labour and the labour unions, a proposal eventually rejected even by Lenin as being too extreme. Trotsky was responsible for smashing the Kronstadt rebellion in 1921. The rebels demanded free elections to the soviets, and legalization of socialist opposition parties. Trotsky and the Red Army also suppressed the anarchist Makhnovist movement in the Ukraine, despite the fact that Makhno never collaborated with the White Guards or the Ukrainian nationalists, and occasionally even allied himself with the Bolsheviks. It's also a well-known fact that Trotsky supported the ban on factions within the Bolshevik Party in 1921. In a speech at the tenth party congress, Trotsky attacked the Workers' Opposition with the famous words: "In the final analysis, the party is always right". He would also support the suppression of a strike wave a few years later by the secret police.

Even in opposition, Trotsky at first didn't call for democracy. Probably, he hoped to swiftly capture the leadership of the Communist Party himself. Thus, the famous Left Opposition of the 1920's never called for free elections to the soviets. (Note the irony when the Left Opposition was accused of breaking the ban on factions supported by Trotsky just a few years earlier.) When Zinoviev and Kamenev, hardly democrats either, fell out with Stalin, Trotsky formed the United Opposition together with them. While the differences between the various Communist factions were real enough, they did not touch upon the question of democracy or "workers' democracy".

How did Trotsky acquire the reputation for being a democrat? The reason is his expulsion from the Soviet Union in 1929, and the formation of an independent Trotskyist movement. In order to overthrow Stalin's regime by a "political revolution", Trotsky now suddenly began demanding - wait for it - free elections to the soviets and legalization of socialist opposition parties. In his book "Literature and revolution", he also demanded artistic freedom. Modern editions of the book include a manifesto co-signed by Trotsky and the Surrealist painter André Breton. Under Lenin, the Bolsheviks were "for" artistic freedom in the sense that they didn't care about art styles, as long as the message was Communist. This explains why Cubism or Futurism could flourish under Lenin. Later, Stalin made "socialist realism" the only approved style. This made it possible for Trotsky to put himself forward as a champion of artistic freedom. Of course, this was all a tactical move. Even during this period, Trotsky defended the suppression of opposition parties during the Russian civil war, calling it a "temporary expediency". He also defended the suppression of Kronstadt, calling it "a mere episode". We can therefore conclude that Trotsky wasn't the democratic socialist he is often portrayed as being by the current leadership of the Fourth International and other "soft" groups.

It could be argued, of course, that "democracy" in the abstract isn't the be all and end all of things political. The American revolution wasn't "democratic" in the modern sense of the term, and neither was the suppression of slavery in the Old South following the victory of the Union. Trotsky's opponent in the Ukraine, Nestor Makhno, wasn't particularly democratic either (see my review of Peter Arshinov's book on the Makhnovist movement). Yet, by championing private or co-operative property in land, the Makhnovists nevertheless gave the peasants more extensive freedom of motion than did the Bolsheviks with their War Communism. Indeed, if the state apparatus takes over all the economy (essentially everything), it's difficult to see how you can have *any* freedom of motion at all, let alone "worker's democracy". Trotsky tried to have it both ways: both a centralized planned economy and free elections to the soviets, a type of regime that hasn't existed anywhere. However, this is not a conclusion "soft" Trotskyists wish to draw. To them, a socialist revolution simply must look like a romanticized version of Spain 1936 or Sandinista Nicaragua 1979-90. By portraying Trotsky as a radical democrat rather than as the sectarian Communist he arguably was, "soft" Trotskyists are vulnerable to criticism from even softer leftists or regular liberal democrats.

TROTSKY AND THE PERMANENT REVOLUTION

Trotsky is mostly associated with the theory of permanent revolution, a theory he (curiously) proposed already before becoming a Bolshevik. He abandoned it during his years in power, only to launch a Bolshevized version of it during the factional struggles following Lenin's death.

The term "permanent revolution" is frequently misunderstood, many people wrongly associating it with the Maoist cultural revolution. Actually, the theory simply says that a successful socialist revolution must be lead by a Communist party rooted in the urban proletariat, even in nations where the proletariat is numerically weak. This will enable (or force) the revolution to become socialist, rather than simply nationalist or democratic. The theory further states that the revolution has to be extended internationally, since socialism in one country is impossible.

The October Revolution in Russia could *perhaps* be seen as a permanent revolution, but it's interesting to note that Lenin didn't see it that way, something Trotsky also had to admit. No other socialist revolution has turned out the way Trotsky predicted. Indeed, no other socialist revolution was based on the urban proletariat! The revolutions in China, Vietnam and other Asian nations were led by middle class cadre and based on the peasantry. Most of Eastern Europe became socialist when dominated by Stalin's Soviet Union. Cuba became socialist after a small nationalist group around Fidel Castro simply stepped in during a power vacuum. In some nations, socialism was established by military officers: Ethiopia, Libya, Burma and Syria. And, of course, no socialist revolution was ever led by Trotskyists! One of the reasons why Trotskyism remained small after World War II was precisely their sectarianism towards the really existing socialist revolutions, which they simply couldn't understand, since these weren't "permanent revolutions". (Less sectarian Trotskyists who wanted to support the revolutions simply declared them "permanent revolutions" anyway!)

As a necessary corollary to permanent revolution, Trotsky also opposed the popular front, the Communist strategy usually associated with the seventh congress of the Comintern in 1935. Lenin had supported something akin to the popular front in "Third World" nations, but Trotsky eventually rejected the idea. At the time, Trotsky's position seemed to be confirmed by events. The idea that Communists could strike a bargain with "bourgeois" forces proved to be a failure during the 1920's and 1930's, as the "allies" usually turned on the Communists, even massacring them. This happened in Turkey, Iran and China. (In Croatia, the "bourgeois" allies also broke with the Communists, but weren't in a position to actually kill them.) In Spain, the popular front was successful, but only at the price of *not* carrying out a socialist revolution, and in the end, the Republic was defeated by Franco anyway. During and after World War II, however, popular fronts were successful in some nations, and less successful in others, making it less clear why Marxists should reject the strategy en toto. Provided that the Communists controlled the regular army, the security forces or a strong guerrilla army with base areas, popular fronts could be used to extend their influence over non-Communist sectors, eventually taking all power themselves. Once again, Trotskyists were sidelined, as they continued their anachronistic opposition to popular fronts as such.

POST-TROTSKY TROTSKYISM

The most successful Trotskyists have been those who broke with Trotsky's sectarian ideas, in deed if not always in word. Thus, the LSSP in Sri Lanka (during a period one of the major political parties in that nation) formed a de facto popular front with the "bourgeois" populist SLFP, eventually even entering a coalition government with it. The Fourth International responded by having the LSSP expelled! In Vietnam, the Trotskyist leader Ta Thu Thau formed another popular front, and became quite successful until his assassination by the Stalinists in 1945. In Bolivia, the Trotskyist POR supported the nationalist MNR and co-operated closely with labour union leaders, while apparently having few actual members "on the floor". POR's influence seems to have been short lived, however. Other Trotskyist groups have attempted to gain a following by mimicking the politics of more popular movements, co-operating with other left-wing groups, or even breaking with Trotskyism altogether. These strategies have sometimes been moderately successful.

Meanwhile, the smaller Trotskyist groups continue with their sectarian posturing, and some of these have developed into pretty weird directions, such as David North's group, which claims that leading American Trotskyists are actually KGB or FBI agents. There is also the now defunct group around Juan Posadas, who believed that UFOs were socialist, and called on Brezhnev to nuke America. Or so the grapevine says. Another notorious bunch of erratic sectarians is the Spartacist League, which supported Jaruzelski, Andropov, Rutskoy and the porn star Nina Hartley. They are less keen on David North, however.

But I'm digressing...

Leon Trotsky was no idiot. Many of his analyses seemed to hold water during the 1920's and 1930's (at least from a Marxist perspective). Stalin's course was frequently erratic, his purges killed most "Old Bolsheviks", while the Comintern (backed up by the GPU) worked hard to contain or stop revolutions, such as the one in Spain. Stalin's regime became progressively worse, more bureaucratic and fascistic during the 1930's. The more specifically Trotskyist problems came later, when world history took a course Trotsky hadn't predicted and his scattered followers apparently weren't prepared for. Today, the legacy of Trotsky is to large extent a legacy spent.

Of course, Marxism itself is problematic, too. But that is another show, as they say.

Almost immediately after his expulsion from the USSR, Trotsky had begun to organize his own Communist movement, which adopted the name Fourth International in 1938. Although Trotsky never called his movement "Trotskyist" but rather "Bolshevik-Leninist", the term "Trotskyist" was proudly adopted by his supporters at some point after the old man's death. Today, the Trotskyist movement is split in many different organizations with widely divergent politics. Only in three nations did Trotskyism approach something close to mass influence: Vietnam during the 1940's, Sri Lanka during the 1940's and 1950's, and Bolivia during the same period. However, Trotskyism has been an important force on the "far left" in both Western Europe, North America and Latin America.

Trotsky's most important political works are "The Third International after Lenin", "The Permanent Revolution", "The Revolution Betrayed", "Literature and revolution", "The Transitional Program" and "In Defence of Marxism". His autobiography "My Life" is also quite well known.

So what is wrong with Trotskyism, then?

To simplify somewhat, there are basically two kinds of Trotskyists. Let's call them "soft" Trotskyists and "hard" Trotskyists. The former category looks upon Trotsky as a democratic socialist, an advocate of a socialism with a human face, indeed, as the first Soviet dissident. They associate him with "workers' democracy" and artistic freedom. In other words, they paint Trotsky as a democratic opponent of Stalin and Stalinism. Today, the official Fourth International takes this "soft" position. The "hard" Trotskyists, by contrast, emphasize Trotsky's similarities with Lenin: his Communism, internationalism and belief in the international proletariat. In this vision, Trotsky is a revolutionary opponent of Stalinism. Thus, we have a moderate version of Trotskyism, and a more militant version.

TROTSKY AS "DEMOCRAT"...AND DICTATOR

The view of Trotsky as a "democrat" is difficult to take seriously. Trotsky's record while in power, and even afterwards, is hardly that of a "democrat".

During the Russian civil war, Trotsky authored the book "Terrorism and Communism", in which he admitted that effective power in Soviet Russia was in the hands of a small group of revolutionary leaders. He considered this a positive trait of the new regime. Commenting on those who compared Russian War Communism with slavery, Trotsky wrote that even slavery was once historically progressive! It should be noted that this book was translated to many different languages (including Swedish and English) and distributed all around the world. Thus, it enjoyed imprimatur from the other Bolshevik leaders and the Communist International. Today, however, the "soft" Trotskyists never reprint it, and even the "hard" groups usually avoid it as too outspoken. (One exception was the Workers Revolutionary Party in Britain. I have reviewed their edition elsewhere.)

Still, Trotsky's actions speak louder than his words. He proposed the militarization of labour and the labour unions, a proposal eventually rejected even by Lenin as being too extreme. Trotsky was responsible for smashing the Kronstadt rebellion in 1921. The rebels demanded free elections to the soviets, and legalization of socialist opposition parties. Trotsky and the Red Army also suppressed the anarchist Makhnovist movement in the Ukraine, despite the fact that Makhno never collaborated with the White Guards or the Ukrainian nationalists, and occasionally even allied himself with the Bolsheviks. It's also a well-known fact that Trotsky supported the ban on factions within the Bolshevik Party in 1921. In a speech at the tenth party congress, Trotsky attacked the Workers' Opposition with the famous words: "In the final analysis, the party is always right". He would also support the suppression of a strike wave a few years later by the secret police.

Even in opposition, Trotsky at first didn't call for democracy. Probably, he hoped to swiftly capture the leadership of the Communist Party himself. Thus, the famous Left Opposition of the 1920's never called for free elections to the soviets. (Note the irony when the Left Opposition was accused of breaking the ban on factions supported by Trotsky just a few years earlier.) When Zinoviev and Kamenev, hardly democrats either, fell out with Stalin, Trotsky formed the United Opposition together with them. While the differences between the various Communist factions were real enough, they did not touch upon the question of democracy or "workers' democracy".

How did Trotsky acquire the reputation for being a democrat? The reason is his expulsion from the Soviet Union in 1929, and the formation of an independent Trotskyist movement. In order to overthrow Stalin's regime by a "political revolution", Trotsky now suddenly began demanding - wait for it - free elections to the soviets and legalization of socialist opposition parties. In his book "Literature and revolution", he also demanded artistic freedom. Modern editions of the book include a manifesto co-signed by Trotsky and the Surrealist painter André Breton. Under Lenin, the Bolsheviks were "for" artistic freedom in the sense that they didn't care about art styles, as long as the message was Communist. This explains why Cubism or Futurism could flourish under Lenin. Later, Stalin made "socialist realism" the only approved style. This made it possible for Trotsky to put himself forward as a champion of artistic freedom. Of course, this was all a tactical move. Even during this period, Trotsky defended the suppression of opposition parties during the Russian civil war, calling it a "temporary expediency". He also defended the suppression of Kronstadt, calling it "a mere episode". We can therefore conclude that Trotsky wasn't the democratic socialist he is often portrayed as being by the current leadership of the Fourth International and other "soft" groups.

It could be argued, of course, that "democracy" in the abstract isn't the be all and end all of things political. The American revolution wasn't "democratic" in the modern sense of the term, and neither was the suppression of slavery in the Old South following the victory of the Union. Trotsky's opponent in the Ukraine, Nestor Makhno, wasn't particularly democratic either (see my review of Peter Arshinov's book on the Makhnovist movement). Yet, by championing private or co-operative property in land, the Makhnovists nevertheless gave the peasants more extensive freedom of motion than did the Bolsheviks with their War Communism. Indeed, if the state apparatus takes over all the economy (essentially everything), it's difficult to see how you can have *any* freedom of motion at all, let alone "worker's democracy". Trotsky tried to have it both ways: both a centralized planned economy and free elections to the soviets, a type of regime that hasn't existed anywhere. However, this is not a conclusion "soft" Trotskyists wish to draw. To them, a socialist revolution simply must look like a romanticized version of Spain 1936 or Sandinista Nicaragua 1979-90. By portraying Trotsky as a radical democrat rather than as the sectarian Communist he arguably was, "soft" Trotskyists are vulnerable to criticism from even softer leftists or regular liberal democrats.

TROTSKY AND THE PERMANENT REVOLUTION

Trotsky is mostly associated with the theory of permanent revolution, a theory he (curiously) proposed already before becoming a Bolshevik. He abandoned it during his years in power, only to launch a Bolshevized version of it during the factional struggles following Lenin's death.

The term "permanent revolution" is frequently misunderstood, many people wrongly associating it with the Maoist cultural revolution. Actually, the theory simply says that a successful socialist revolution must be lead by a Communist party rooted in the urban proletariat, even in nations where the proletariat is numerically weak. This will enable (or force) the revolution to become socialist, rather than simply nationalist or democratic. The theory further states that the revolution has to be extended internationally, since socialism in one country is impossible.

The October Revolution in Russia could *perhaps* be seen as a permanent revolution, but it's interesting to note that Lenin didn't see it that way, something Trotsky also had to admit. No other socialist revolution has turned out the way Trotsky predicted. Indeed, no other socialist revolution was based on the urban proletariat! The revolutions in China, Vietnam and other Asian nations were led by middle class cadre and based on the peasantry. Most of Eastern Europe became socialist when dominated by Stalin's Soviet Union. Cuba became socialist after a small nationalist group around Fidel Castro simply stepped in during a power vacuum. In some nations, socialism was established by military officers: Ethiopia, Libya, Burma and Syria. And, of course, no socialist revolution was ever led by Trotskyists! One of the reasons why Trotskyism remained small after World War II was precisely their sectarianism towards the really existing socialist revolutions, which they simply couldn't understand, since these weren't "permanent revolutions". (Less sectarian Trotskyists who wanted to support the revolutions simply declared them "permanent revolutions" anyway!)

As a necessary corollary to permanent revolution, Trotsky also opposed the popular front, the Communist strategy usually associated with the seventh congress of the Comintern in 1935. Lenin had supported something akin to the popular front in "Third World" nations, but Trotsky eventually rejected the idea. At the time, Trotsky's position seemed to be confirmed by events. The idea that Communists could strike a bargain with "bourgeois" forces proved to be a failure during the 1920's and 1930's, as the "allies" usually turned on the Communists, even massacring them. This happened in Turkey, Iran and China. (In Croatia, the "bourgeois" allies also broke with the Communists, but weren't in a position to actually kill them.) In Spain, the popular front was successful, but only at the price of *not* carrying out a socialist revolution, and in the end, the Republic was defeated by Franco anyway. During and after World War II, however, popular fronts were successful in some nations, and less successful in others, making it less clear why Marxists should reject the strategy en toto. Provided that the Communists controlled the regular army, the security forces or a strong guerrilla army with base areas, popular fronts could be used to extend their influence over non-Communist sectors, eventually taking all power themselves. Once again, Trotskyists were sidelined, as they continued their anachronistic opposition to popular fronts as such.

POST-TROTSKY TROTSKYISM

The most successful Trotskyists have been those who broke with Trotsky's sectarian ideas, in deed if not always in word. Thus, the LSSP in Sri Lanka (during a period one of the major political parties in that nation) formed a de facto popular front with the "bourgeois" populist SLFP, eventually even entering a coalition government with it. The Fourth International responded by having the LSSP expelled! In Vietnam, the Trotskyist leader Ta Thu Thau formed another popular front, and became quite successful until his assassination by the Stalinists in 1945. In Bolivia, the Trotskyist POR supported the nationalist MNR and co-operated closely with labour union leaders, while apparently having few actual members "on the floor". POR's influence seems to have been short lived, however. Other Trotskyist groups have attempted to gain a following by mimicking the politics of more popular movements, co-operating with other left-wing groups, or even breaking with Trotskyism altogether. These strategies have sometimes been moderately successful.

Meanwhile, the smaller Trotskyist groups continue with their sectarian posturing, and some of these have developed into pretty weird directions, such as David North's group, which claims that leading American Trotskyists are actually KGB or FBI agents. There is also the now defunct group around Juan Posadas, who believed that UFOs were socialist, and called on Brezhnev to nuke America. Or so the grapevine says. Another notorious bunch of erratic sectarians is the Spartacist League, which supported Jaruzelski, Andropov, Rutskoy and the porn star Nina Hartley. They are less keen on David North, however.

But I'm digressing...

Leon Trotsky was no idiot. Many of his analyses seemed to hold water during the 1920's and 1930's (at least from a Marxist perspective). Stalin's course was frequently erratic, his purges killed most "Old Bolsheviks", while the Comintern (backed up by the GPU) worked hard to contain or stop revolutions, such as the one in Spain. Stalin's regime became progressively worse, more bureaucratic and fascistic during the 1930's. The more specifically Trotskyist problems came later, when world history took a course Trotsky hadn't predicted and his scattered followers apparently weren't prepared for. Today, the legacy of Trotsky is to large extent a legacy spent.

Of course, Marxism itself is problematic, too. But that is another show, as they say.

No comments:

Post a Comment