"Sherlock" is a BBC mini-series in three

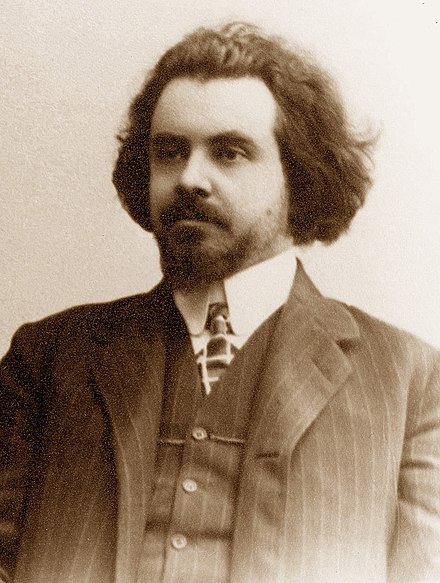

episodes. The concept is simple but interesting. What would happen if Sherlock

Holmes and Dr. Watson had lived today, in 21st century London? This modern

version of Arthur Conan Doyle's novels was the most popular TV series in

Britain last year. Since it ends with a cliff-hanger, I assume new episodes

will be produced eventually.

Personally, I was somewhat disappointed by the series. The first episode, "A study in pink" is excellent, but the two remaining episodes didn't live up to my high expectations. I would give "A study in pink" five stars, and the two other episodes three stars at best. And yes, this seems to be a minority opinion. Everyone else loves the entire series...

In "Sherlock", Dr. Watson is a war veteran from Afghanistan, while Holmes is a real freak. The master detective comes across as a hyperactive, histrionic teenager spouting a Dr. Who hairdo. He has some disturbing sociopathic tendencies as well. Frankly, he's crazier than Jeremy Brett's interpretation of Sherlock Holmes in the classical Granada TV series! Both Holmes and Watson look strangely out of place in 21st century London, giving the series a somewhat unnatural feel. It feels more like science fiction than realism. "Sherlock" also pokes fun at various Sherlock Holmes stereotypes, as when Holmes (an cocaine addict in the original novels) uses nicotine patches to stimulate his thinking, or when people assume that Dr. Watson and Holmes must be gay, since they share a flat together at Baker Street.

Don't get me wrong. These are the things I *liked* about the series. My real problem is the plot development...

In the first episode (the good one), Holmes and Watson chases a serial killer who makes John Doe from "Seven" look like an amateur. The episode contains a number of unexpected twists. This is also the episode which introduces the various characters in their modern settings. In the second episode, the suspected criminals are a group of Chinese, who look and act like 18th century Western stereotypes of Chinese. The whole thing feels contrived and frankly ridiculous. But the real let down is the confusing third episode, which introduces Moriarty. The criminal mastermind looks like a parody of Keyser Söze or something to that effect. *That's* Moriarty? You gotta be kidding, Miss Hudson!

As already mentioned, the whole series ends with a cliff-hanger, but I suppose both Holmes and Watson somehow makes it through, since a new season has been commissioned by the BBC.

Since most people like "Sherlock", chances are you will as well. Personally, however, I was disappointed by the contrast between the excellent pilot and the remaining two episodes.

I'll the series as a whole three stars and await further developments...

This was of course a review of the first season. We all know what happened next, don´t we? Yes, Cumberbatch became so famous that he got a starring role in...Star Trek! :D

.jpg)